Kalachuris of Mahishmati | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 550 CE–c. 625 CE | |||||||||||||||||||||

Silver coin of king Krishnaraja (r. c. 550-575) of the Kalachuri dynasty, on the model of the Western Satraps.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

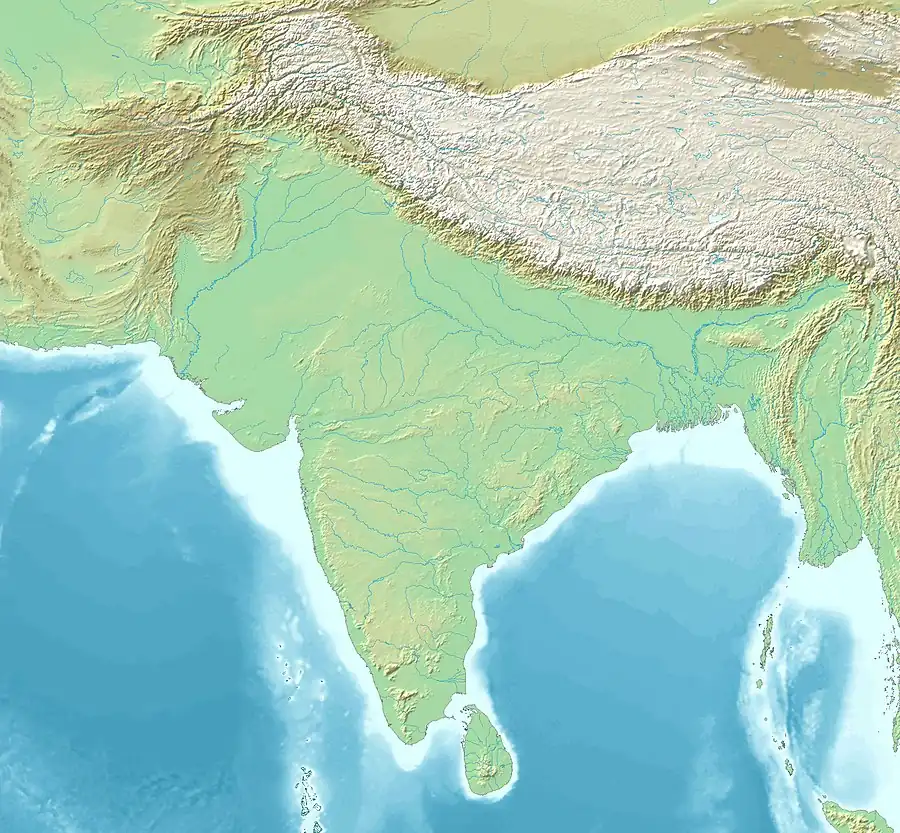

South-Asia 600 CE MAPS -500 -150 120 350 500 600 800 1000 1175 1250 1400 1500 Map of the Early Kalachuris and neighbouring polities circa 600 CE.[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mahishmati | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Shaivism | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 550 CE | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 625 CE | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||||||||||||

The Kalachuris (IAST: Kalacuri), also known as Kalachuris of Mahishmati, were an Indian dynasty that ruled in west-central India between 6th and 7th centuries. They are also known as the Early Kalachuris to distinguish them from their later namesakes, especially the Kalachuris of Tripuri. Their territory included parts of present-day Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra. Their capital was located at Mahishmati. Epigraphic and numismatic evidence suggests that the earliest of the Ellora and Elephanta cave monuments were built during the Kalachuri rule.

In the 6th century, the Kalachuris gained control of the territories formerly ruled by the Guptas, the Vakatakas and the Vishnukundinas. Only three Kalachuri kings are known from inscriptional evidence: Shankaragana, Krishnaraja, and Buddharaja. The Kalachuris lost their power to the Chalukyas of Vatapi in the 7th century.

Origin

Historians often agree on the opinion that, they were a continuation of Traikutaka dynasty (or Abhira-Traikutakas)[2][3] of Konkan because after decline of their rule in Konkan they retired to Central Provinces and started calling themselves Haihaya and Kalachuri.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

The Abhira origin[11] of Early Kalachuris can also be confirmed via Ishwarsena's era. As Ishwarsena was an Abhira ruler and the era which he started was called Abhira-Traikutaka-Kalachuri-Chedi era[12][13] in the Indian history.[14]

Territory

According to the Kalachuri inscriptions, the dynasty controlled Ujjayini, Vidisha and Anandapura. Literary references suggest that their capital was located at Mahishmati in the Malwa region.[17]

The dynasty also controlled Vidarbha, where they succeeded the Vakataka and the Vishnukundina dynasties.[17]

In addition, the Kalachuris conquered northern Konkan (around Elephanta) by the mid-6th century. Here, they succeeded the Traikutaka dynasty.[17]

History

Krishnaraja

Krishnaraja (r. c. 550-575) is the earliest known Kalachuri ruler, and probably established the dynasty with its capital at Mahishmati. The political situation in the region around 550 CE likely favoured him: the death of Yashodharman left a political vacuum in Malwa, the Vakataka rule had ended in Maharashtra, and the Maitraka power was declining in Gujarat.[18]

No inscriptions of Krishnaraja survive, but his coins have been found at several places, including in present-day Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra. The find spots cover a vast region extending from Rajasthan in north to Satara district in the south, and from Mumbai (Salsette) in the west to Amaravati district in the west. These coins seem to have remained in circulation for nearly 150 years after his death, as evident from the 710-711 CE (Kalachuri year 461) Anjaneri copper plate inscription of Bhogashakti, which calls them "Krishnaraja-rupaka". Therefore, it is not certain if Krishnaraja's rule extended over this entire territory, or if these coins traveled to distant places after his death.[18]

Krishnaraja's extant coins are all of silver, round in shape, and 29 grains in weight. They imitate the design of the coins issued by the earlier dynasties including the Western Kshatrapas, the Traikutakas, and the Guptas. The obverse features a bust of the king facing right, and the reverse features a figure of Nandi, the bull vahana of the Hindu god Shiva.[18] The Nandi design is based on the coins issued by the Gupta king Skandagupta.[17]

A Brahmi script legend describing the king as a devotee of Shiva (Parama-maheshvara) surrounds the Nandi figure on his coins.[18] An inscription of his son Shankaragana also describes him as a devotee of Pashupati (an aspect of Shiva) since his birth.[17] Historical evidence suggests that he may have commissioned the Shaivite monuments at the Elephanta Caves and the earliest of the Brahmanical caves at Ellora, where his coins have been discovered.[19][20][17]

Shankaragana

Shankaragana (r. c. 575-600) is the earliest ruler of the dynasty to be attested by his own inscriptions, which were issued from Ujjain and Nirgundipadraka. His Ujjain grant is the earliest epigraphic record of the dynasty.[21]

Shakaragana's adopted the titles of the Gupta emperor Skandagupta. This suggests that he conquered western Malwa, which was formerly under the Gupta authority. His kingdom probably also included parts of the present-day Gujarat.[21]

Like his father, Shankaragana described himself as a Parama-Maheshvara (devotee of Shiva).[21]

Buddharaja

Buddharaja is the last known ruler of the early Kalachuri dynasty. He was a son of Shankaragana.[21]

Buddharaja conquered eastern Malwa, but he probably lost western Malwa to the ruler of Vallabhi. During his reign, the Chalukya king Mangalesha attacked the Kalachuri kingdom from the south, sometime after 600 CE. The invasion did not result in a complete conquest, as evident by Buddharaja's 609-610 CE (360 KE) Vidisha and 610-611 CE (361 KE) Anandapura grants.[21] Buddharaja probably lost his sovereignty during a second Chalukya invasion, by Mangalesha,[22] or by his nephew Pulakeshin II.[21] The Chalukya inscriptions mention that Mangalesha defeated the Kalachuris, but do not credit Pulakeshin with this achievement; therefore, it is likely that Mangalesha was the Chalukya ruler responsible for ending the Kalachuri power.[22]

Like his father and grandfather, Buddharaja described himself as a Parama-Maheshvara (devotee of Shiva). His queen Ananta-Mahayi belonged to the Pashupata sect.[21]

Descendants

No concrete information is available about the successors of Buddharaja, but it is known that by 687 CE, the Kalachuris had become feudatories of the Chalukyas.[21]

An inscription issued by a prince named Taralasvamin was found at Sankheda (where one of Shankaragana's grants was also found). This inscription describes Taralasvamin as a devotee of Shiva, and his father Maharaja Nanna as a member of the "Katachchuri" family. The inscription is dated to the year 346 of an unspecified era. Assuming the era as Kalachuri era, Taralasvamin would have been a contemporary of Shankaragana. However, Taralasvamin and Nanna are not mentioned in other Kalachuri records. Also, unlike other Kalachuri inscriptions, the date in this inscription is mentioned in decimal numbers. Moreover, some expressions in the inscription appear to have been borrowed from the 7th century Sendraka inscriptions. Because of these evidences, V. V. Mirashi considered Taralasvamin's inscription as a spurious one.[23]

V. V. Mirashi connected the Kalachuris of Tripuri to the early Kalachuri dynasty. He theorizes that the early Kalachuris moved their capital from Mahishmati to Kalanjara, and from there to Tripuri.[24]

Cultural contributions

Elephanta

The Elephanta Caves which contain Shaivite monuments are located along the Konkan coast, on the Elephanta Island near Mumbai. Historical evidence suggests that these monuments are associated with Krishnaraja, who was also a Shaivite.[20]

The Kalachuris appear to have been the rulers of the Konkan coast, when some of the Elephanta monuments were built.[20] Silver coins of Krishnaraja have been found along the Konkan coast, on the Salsette Island (now part of Mumbai) and in the Nashik district.[20] Around 31 of his copper coins have been found on the Elephanta Island, which suggests that he was the patron of the main cave temple on the island.[19] According to numismatist Shobhana Gokhale, these low-value coins may have been used to pay the wages of the workers involved in the cave excavation.[21]

Ellora

.jpg.webp)

The earliest of the Hindu caves at Ellora appear to have been built during the Kalachuri reign, and possibly under Kalachuri patronage. For example, the Ellora Cave No. 29 shows architectural and iconographic similarities with the Elephanta Caves.[20] The earliest coin found at Ellora, in front of Cave No. 21 (Rameshvara), was issued by Krishnaraja.[17]

Rulers

The following are the known rulers of the Kalachuri dynasty of Malwa with their estimated reigns (IAST names in brackets):[25]

- Krishnaraja (Kṛṣṇarāja), r. c. 550-575 CE

- Shankaragana (Śaṃkaragaṇa), r. c. 575-600 CE

- Buddharaja (Buddharāja), r. c. 600-625 CE

See also

- Kalachuri Era, used by the Kalachuris and so named after them

References

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 146, map XIV.2 (b). ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ Prācī-jyoti: Digest of Indological Studies. Kurukshetra University. 1990.

- ↑ Vaidya C. V. (1921). History Of Medieval Hindu India.

- ↑ Compte-rendu de la ... Session. Le Congrès. 1888.

- ↑ Proceedings. 1889.

- ↑ Proceedings (in French). 1968.

- ↑ Vaidya, Chintaman Vinayak (1921). History of Mediæval Hindu India: Circa 600-800 A.D. Oriental Book Supplying Agency.

- ↑ Singh, Nagendra Kr (2001). Encyclopaedia of Jainism. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-261-0691-2.

- ↑ Solanki, A. N. (1976). The Dhodias: A Tribe of South Gujarat Area. Maria Enzersdorf : Elisabeth Stiglmayr.

- ↑ India), Oriental Institute (Vadodara (1981). Journal of the Oriental Institute. Oriental Institute, Maharajah Sayajirao University.

- ↑ Siṃhadeba, Jitāmitra Prasāda (2006). Archaeology of Orissa: With Special Reference to Nuapada and Kalahandi. R.N. Bhattacharya. ISBN 978-81-87661-50-4.

- ↑ Choubey, M. C. (2006). Tripurī, History and Culture. Sharada Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-88934-28-7.

- ↑ Mirashi Vasudev Vishnu. (1955). Inscriptions Of The Kalachuri-chedi Era Vol-iv Part-i (1955). Government Epigraphist For India.

- ↑ Chattopadhyaya, Sudhakar (1974). Some Early Dynasties of South India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2941-1.

- ↑ Om Prakash Misra 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ Charles Dillard Collins 1988, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Charles Dillard Collins 1988, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 R. K. Sharma 1980, p. 4.

- 1 2 Charles Dillard Collins 1988, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Geri Hockfield Malandra 1993, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Charles Dillard Collins 1988, p. 10.

- 1 2 Durga Prasad Dikshit 1980, p. 57.

- ↑ Charles Dillard Collins 1988, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ V. V. Mirashi 1974, p. 376.

- ↑ Ronald M. Davidson 2012, p. 37.

Bibliography

- Charles Dillard Collins (1988). The Iconography and Ritual of Siva at Elephanta. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780887067730.

- Durga Prasad Dikshit (1980). Political History of the Chālukyas of Badami. Abhinav. OCLC 8313041.

- Geri Hockfield Malandra (1993). Unfolding A Mandala: The Buddhist Cave Temples at Ellora. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791413555.

- Om Prakash Misra (2003). Archaeological Excavations in Central India: Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-874-7.

- R. K. Sharma (1980). The Kalachuris and their times. Sundeep. OCLC 7816720.

- Ronald M. Davidson (2012). Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231501026.

- V. V. Mirashi (1974). Bhavabhuti. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120811805.

.jpg.webp)