JavaScript has a very twisted form of prototypal inheritance. I like to call it the constructor pattern of prototypal inheritance. There is another pattern of prototypal inheritance as well - the prototypal pattern of prototypal inheritance. I'll explain the latter first.

In JavaScript objects inherit from objects. There's no need for classes. This is a good thing. It makes life easier. For example say we have a class for lines:

class Line {

int x1, y1, x2, y2;

public:

Line(int x1, int y1, int x2, int y2) {

this.x1 = x1;

this.y1 = y1;

this.x2 = x2;

this.y2 = y2;

}

int length() {

int dx = x2 - x1;

int dy = y2 - y1;

return sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

}

Yes, this is C++. Now that we created a class we may now create objects:

Line line1(0, 0, 0, 100);

Line line2(0, 100, 100, 100);

Line line3(100, 100, 100, 0);

Line line4(100, 0, 0, 0);

These four lines form a square.

JavaScript doesn't have any classes. It has prototypal inheritance. If you wanted to do the same thing using the prototypal pattern you would do this:

var line = {

create: function (x1, y1, x2, y2) {

var line = Object.create(this);

line.x1 = x1;

line.y1 = y1;

line.x2 = x2;

line.y2 = y2;

return line;

},

length: function () {

var dx = this.x2 - this.x1;

var dy = this.y2 - this.y1;

return Math.sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

};

Then you create instances of the object line as follows:

var line1 = line.create(0, 0, 0, 100);

var line2 = line.create(0, 100, 100, 100);

var line3 = line.create(100, 100, 100, 0);

var line4 = line.create(100, 0, 0, 0);

That's all there is to it. No confusing constructor functions with prototype properties. The only function needed for inheritance is Object.create. This function takes an object (the prototype) and returns another object which inherits from the prototype.

Unfortunately, unlike Lua, JavaScript endorses the constructor pattern of prototypal inheritance which makes it more difficult to understand prototypal inheritance. The constructor pattern is the inverse of the prototypal pattern.

- In the prototypal pattern objects are given the most importance. Hence it's easy to see that objects inherit from other objects.

- In the constructor pattern functions are given the most importance. Hence people tend to think that constructors inherit from other constructors. This is wrong.

The above program would look like this when written using the constructor pattern:

function Line(x1, y1, x2, y2) {

this.x1 = x1;

this.y1 = y1;

this.x2 = x2;

this.y2 = y2;

}

Line.prototype.length = function () {

var dx = this.x2 - this.x1;

var dy = this.y2 - this.y1;

return Math.sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

};

You may now create instances of Line.prototype as follows:

var line1 = new Line(0, 0, 0, 100);

var line2 = new Line(0, 100, 100, 100);

var line3 = new Line(100, 100, 100, 0);

var line4 = new Line(100, 0, 0, 0);

Notice the similarity between the constructor pattern and the prototypal pattern?

- In the prototypal pattern we simply create an object which has a

create method. In the constructor pattern we create a function and JavaScript automatically creates a prototype object for us.

- In the prototypal pattern we have two methods -

create and length. In the constructor pattern too we have two methods - constructor and length.

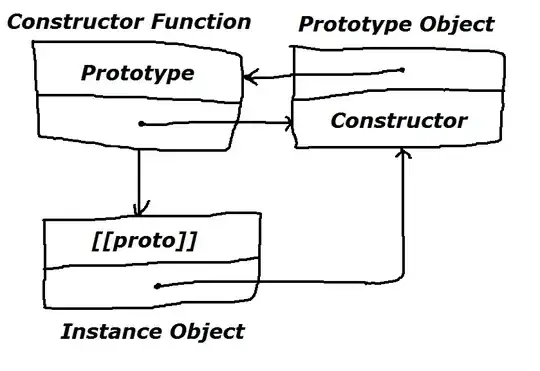

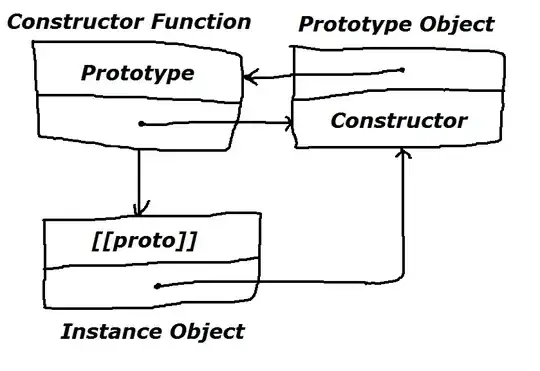

The constructor pattern is the inverse of the prototypal pattern because when you create a function JavaScript automatically creates a prototype object for the function. The prototype object has a property called constructor which points back to the function itself:

As Eric said, the reason console.log knows to output Foo is because when you pass Foo.prototype to console.log:

- It finds

Foo.prototype.constructor which is Foo itself.

- Every named function in JavaScript has a property called

name.

- Hence

Foo.name is "Foo". So it finds the string "Foo" on Foo.prototype.constructor.name.

Edit: Alright, I understand that you have a problem with the redefining the prototype.constructor property in JavaScript. To understand the problem let's first understand how the new operator works.

- First, I want you to take a good look at the diagram I showed you above.

- In the above diagram we have a constructor function, a prototype object and an instance.

- When we create an instance using the

new keyword before a constructor JS creates a new object.

- The internal

[[proto]] property of this new object is set to point to whatever constructor.prototype points to at the time of object creation.

What does this imply? Consider the following program:

function Foo() {}

function Bar() {}

var foo = new Foo;

Foo.prototype = Bar.prototype;

var bar = new Foo;

alert(foo.constructor.name); // Foo

alert(bar.constructor.name); // Bar

See the output here: http://jsfiddle.net/z6b8w/

- The instance

foo inherits from Foo.prototype.

- Hence

foo.constructor.name displays "Foo".

- Then we set

Foo.prototype to Bar.prototype.

- Hence

bar inherits from Bar.prototype although it was created by new Foo.

- Thus

bar.constructor.name is "Bar".

In the JS fiddle you provided you created a function Foo and then set Foo.prototype.constructor to function Bar() {}:

function Foo() {}

Foo.prototype.constructor = function Bar() {};

var f = new Foo;

console.log(f.hasOwnProperty("constructor"));

console.log(f.constructor);

console.log(f);

Because you modified a property of Foo.prototype every instance of Foo.prototype will reflect this change. Hence f.constructor is function Bar() {}. Thus f.constructor.name is "Bar", not "Foo".

See it for yourself - f.constructor.name is "Bar".

Chrome is known to do weird things like that. What's important to understand is that Chrome is a debugging utility and console.log is primarily used for debugging purposes.

Hence when you create a new instance Chrome probably records the original constructor in an internal property which is accessed by console.log. Thus it displays Foo, not Bar.

This is not actual JavaScript behavior. According to the specification when you overwrite the prototype.constructor property there's no link between the instance and the original constructor.

Other JavaScript implementations (like the Opera console, node.js and RingoJS) do the right thing and display Bar. Hence Chrome's behavior is non-standard and browser-specific, so don't panic.

What's important to understand is that even though Chrome displays Foo instead of Bar the constructor property of the object is still function Bar() {} as with other implementations: