It becomes obvious when you consider that the compiler will generate a default constructor, a default copy constructor, and a default copy assignment operator for you, in case your struct/class does not contain reference members. Then, think of that the standard allows you to call member methods on temporaries, that is, you can call non-const members on non-const temporaries.

See this example:

struct Foo {};

Foo foo () {

return Foo();

}

struct Bar {

private:

Bar& operator = (Bar const &); // forbid

};

Bar bar () {

return Bar();

}

int main () {

foo() = Foo(); // okay, called operator=() on non-const temporarie

bar() = Bar(); // error, Bar::operator= is private

}

If you write

struct Foo {};

const Foo foo () { // return a const value

return Foo();

}

int main () {

foo() = Foo(); // error

}

i.e. if you let function foo() return a const temporary, then a compile error occurs.

To make the example complete, here is how to call a member of a const temporarie:

struct Foo {

int bar () const { return 0xFEED; }

int frob () { return 0xFEED; }

};

const Foo foo () {

return Foo();

}

int main () {

foo().bar(); // okay, called const member method

foo().frob(); // error, called non-const member of const temporary

}

You could define the lifetime of a temporary to be within the current expression. And then that's why you can also modify member variables; if you couldn't, than the possibility of being able to call non-const member methods would be led ad absurdum.

edit: And here are the required citations:

12.2 Temporary objects:

- 3) [...] Temporary objects are destroyed as the last step in evaluating the full-expression (1.9) that (lexically) contains the point where they were created. [...]

and then (or better, before)

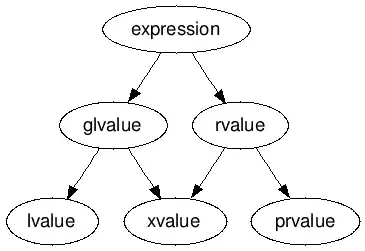

3.10 Lvalues and rvalues:

- 10) An lvalue for an object is necessary in order to modify the object except that an rvalue of class type can also be used to modify its referent under certain circumstances. [Example: a member function called for an object (9.3) can modify the object. ]

And an example use: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/More_C%2B%2B_Idioms/Named_Parameter