In essential skills for the agile developer, in the needs vs capabilities interface, chap, 12, I'm trying to understand the main solution proposed to the challenge of applying the LAW OF DEMETER that the author mention by the end of this chapter.

To make the story short.

We start with the following study case:

public class City {

public string name{};

public City twinCity{};

public Street[] streets{};

}

public class Street {

public string name{};

public House[] houses{};

}

public class House {

public int number{};

public Color color{};

}

Where the author state that:

Models like this encourage us to expose rather than to encapsulate. If your code has a reference to a particular City instance, say one that maps Seattle, and you wanted the color of the house at 1374 Main Street, then you might do something like the following:

public Foo() {

Color c = Seattle.streets()["Main"].

houses()[1374].

color();

}

The problem, if this is done as a general practice, is that the system develops dependencies everywhere, and a change to any part of this model can have effects up and down the chain of these dependencies. That’s where the Law of Demeter, which states2 “Don’t talk to strangers,” comes in. This is formalized in object systems as the Law of Demeter for Functions/Methods. A method M of an object O may only invoke the methods of the following kinds of objects:

- O’s

- M’s parameters

- Any objects instantiated within M

- O’s direct component objects

- Any global variables accessible by O

and suggest that when applying the LAW of DEMTER we should aim for something like

public Foo() {

Color c = Seattle.ColorOfHouseInStreet("Main",1374);

}

and quickly warns from the following:

Although this would seem to be a wise policy initially, it can quickly get out of hand as the interface of any given entity can be expected to provide literally anything it relates to. These interfaces tend to bloat over time, and in fact there would seem to be almost no end to the number of public methods a given glass may eventually support.

Then after a quick detour at explaining the the problem of coupling and dependency, where he mentions the importance of separating a client and its service by the interface of the service, and possibly furthermore by separating the client "needs interface" from the "service capability interface" via the use of an adapter as something ideal but not necessarily practical;

he suggests that to remedy to the problem, we could combine the LAW of DEMETER and the needs/capability separation, using a facade pattern as explain below:

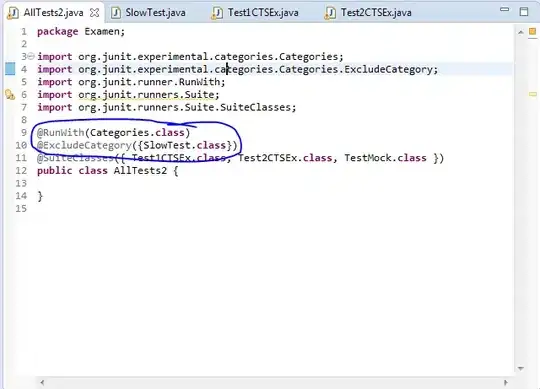

From the original dependency

In applying the law of demeter and the needs/capability interface separation we should initially get:

But given that it is just impractical especially from the point of view of mocking, we could have something simpler with a facade as follow:

The problem is that i just don't see how that exactly solve the problem of not violating the Law of Demeter. I think it maintains the law between the original client and the original service. But it just moved the violation within the FACADE.