I understand that you have

- forked from a project on GitHub,

- cloned your fork,

- made a number of commits in that local repo.

In case you have already pushed to your fork

Because your (untidy) history is now public, some people may have already forked/cloned it to build upon your work. By rewriting your history and then force pushing to your fork, you run the risk of pissing those people off... big time! That's bad practice.

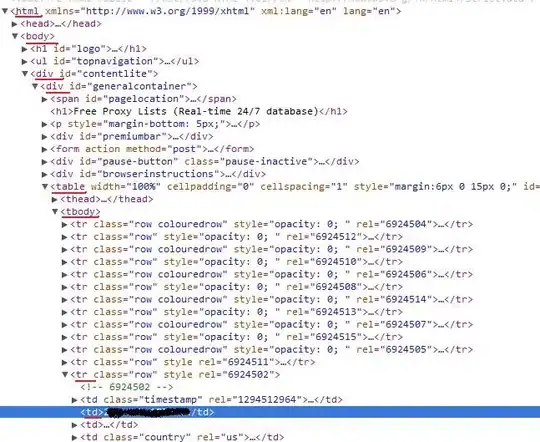

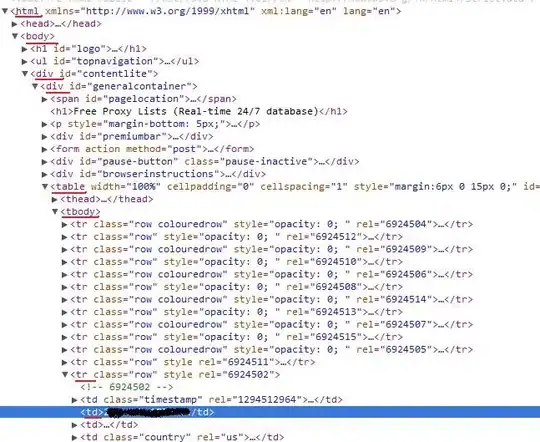

So, before proceeding, you should at least make sure that your project was never forked or cloned. Fortunately, GitHub keeps track of that information. In the right-hand side navigation bar, click on Graphs.

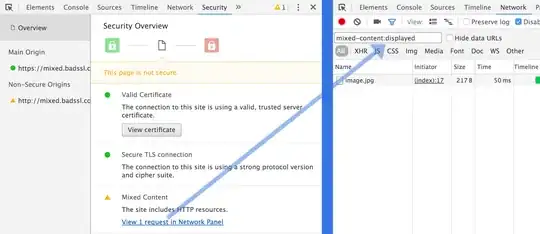

The Network tab will show you how many people forked your project.

If you're the only one listed there, good. Then go to the Traffic tab, to see how many times your project was cloned.

If your project has never been cloned, there is still time to force push your tidied history to your fork.

One caveat: of course, there is always a risk that someone forks/clones your old, untidy history just in the nick of time before you force push. Proceed with care.

In case you have not yet pushed anything to your fork

In that case, rewriting your history is completely safe, and is considered good practice.

All you have to decide is the level detail you wish to retain in the new, tidied history.

It's really up to you, but, as you rewrite history, try to put yourself in the shoes of someone browsing that history and trying to make sense of your improvements/changes.

For instance, if the changes you brought to the original project are substantial, squashing all your commits into one massive commit may not be the best idea... Make your history more pedestrian by spreading your changes over several commits, in a logical manner.

Here is a relevant passage of the Pro Git book:

[...] try to make each commit a logically separate changeset. If you can, try to make your changes digestible — don’t code for a whole weekend on five different issues and then submit them all as one massive commit on Monday. Even if you don’t commit during the weekend, use the staging area on Monday to split your work into at least one commit per issue, with a useful message per commit. If some of the changes modify the same file, try to use git add --patch to partially stage files (covered in detail in Chapter 6). The project snapshot at the tip of the branch is identical whether you do one commit or five, as long as all the changes are added at some point, so try to make things easier on your fellow developers when they have to review your changes. This approach also makes it easier to pull out or revert one of the changesets if you need to later.