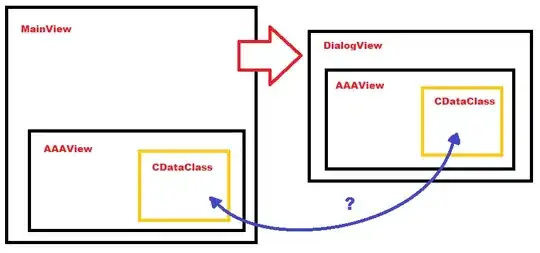

I don't think it's ideal that you've got your application architecture diagrammed as relationships among views; I think a better way to think about it is as a set of relationships among viewmodels, with the views hanging off that tree as needed. When you think about it that way, "how does data get passed" gets a lot simpler. A view is just a conduit between a viewmodel and the user. You don't design a house as a set of windows and telephones and then try to figure out the floor plan from that. You start with what the house does and how people will live in it.

So this is easy:

Some viewmodels have an AAViewModel property. There may be all kinds of simple or complicated views on those viewmodels; if a view wants to let the user edit the viewmodel's AAViewModel stuff, then it includes an AAView bound appropriately to the viewmodel's AAViewModel. Your MainViewModel and DialogViewModel are both big complicated interactive views that want to let somebody edit their vm's AAViewModel stuff.

If MainViewModel is DialogViewModel's parent, or created a temporary instance of DialogViewModel just to put in a modal dialog, then MainViewModel would show the dialog, and have a look at dialogVM.AAVM.CData.IsDirty to decide what to do with it. Or maybe it gives dialogVM.AAVM a new CDataClass instance before showing the dialog (maybe a clone of its own instance), and if ShowModel() returns true, then it does something with dialogVM.AAVM.CData.

The point is that once your viewmodels are driving everything, it becomes relatively simple for them to communicate with each other. Parent-child is easy: Parent gives stuff to the child and looks at what the child brings back. A viewmodel can subscribe to another viewmodel's PropertyChanged event; a parent viewmodel can monitor its children; when something happens on a child, the parent can decide whether to update a sibling. In general, children should not know anything at all about their parents; this makes it much easier to reuse child viewmodels in disparate contexts. It's up to parents to decide what to do with that information.

All AAViewModel knows is that somebody handed him a copy of CDataClass; he updates his public properties accordingly. Then somebody else (probably AAView, but he doesn't know) hands him some changes by setting his properties; he updates his CDataClass instance accordingly. After a while, unknown to him, one viewmodel or another comes and looks at that CDataClass.

And communication between views and viewmodels happens via bindings.

UPDATE

It turns out that you're creating viewmodels in your views, and as a result you have no idea how the parent can get to them. And now you know why it's not a good idea to create child view viewmodels that way.

Here's how you do child view/viewmodels in the viewmodel-centric design I described above:

First, get rid of whatever you're doing to create the child viewmodels inside the view.

Second, create a DataTemplate for the child viewmodel type. This should go in a resource dictionary which is merged into the resources in App.xaml, but it's so simple that it won't kill you if you get lazy and just paste it into the Resources of the two different views where it's used.

I don't know what your namespace declarations look like. I'm going to assume that views are in something called xmlns:view="...", and viewmodels are in something called xmlns:vm="...".

<DataTemplate DataType="{x:Type vm:AAAViewModel}">

<view:AAAView />

</DataTemplate>

Now, you can assign an AAAViewModel to the ContentProperty of any control that inherits from ContentControl (and that's most of them), and the template will be instantiated. That means that XAML will create an AAAView for you and assign that instance of AAAViewModel to the DataContext property of the AAAView that it just created.

So let's create a child AAAViewModel next, and then we'll show it in the UI.

public class DialogViewModel

{

// You can create this in DialogViewModel's constructor if you need to

// give it parameters that won't be known until then.

private AAAViewModel _aaavm = new AAAViewModel();

public AAAViewModel AAAVM

{

get { return _aaavm; }

protected set {

_aaavm = value;

OnPropertyChanged(nameof(AAAVM));

}

}

And now we can display AAAVM in DialogView:

<Grid>

<Grid.RowDefinitions>

<RowDefinition Height="Auto" />

<RowDefinition Height="*" />

</Grid.RowDefinitions>

<ContentControl

Content="{Binding AAAVM}"

Grid.Row="0"

/>

<StackPanel Orientation="Vertical" Grid.Row="1">

<!-- Other stuff -->

</StackPanel>

</Grid>

Now how does MainViewModel get in touch with a DialogViewModel? In the case of dialogs, since they have a finite lifespan, it's not actually a big deal to let them create their own viewmodels. You can do it either way. I generally lean towards having it create its own as in the second example below.

Not quite the same, but close. First, once again, get rid of whatever you're doing where the dialog creates its own viewmodel.

MainViewModel.cs

public CDataClass CDC { /* you know the drill */ }

public void ShowDialog()

{

var dvm = new DialogViewModel();

// Maybe this isn't what you want; I don't know what CDataClass does.

// But I'm assuming it has a copy constructor.

dvm.AAAVM.CDC = new CDataClass(this.CDC);

if (DialogView.ShowDialog(dvm).GetValueOrDefault())

{

CDC = dvm.CDC;

}

}

Note that this next one is view codebehind, not viewmodel.

DialogView.xaml.cs

public static bool? ShowDialog(DialogViewModel dvm)

{

var vw = new DialogView() { DataContext = dvm };

return vw.ShowDialog();

}

Now, you could let the dialog continue creating its own viewmodel; in that case you would give it a public property like this:

public DialogViewModel ViewModel => (DialogViewModel)DataContext;

And a ShowDialog method like this:

DialogView.xaml.cs

public static bool? ShowDialog(CDataClass cdc)

{

var dlg = new DialogView();

dlg.ViewModel.AAAVVM.CDC = cdc;

return dlg.ShowDialog();

}

And then the parent could interact with it like this instead:

MainViewModel.cs

public void ShowDialog()

{

var cdcClone = new CDataClass(this.CDC);

if (DialogView.ShowDialog(cdcClone).GetValueOrDefault())

{

CDC = cdcClone;

}

}

Nice and tidy.

If that dialog isn't modal, make the dialog viewmodel a private member of MainViewModel, and have MainViewModel subscribe to events on the dialog viewmodel to keep abreast of what the dialog is doing. Whenever the user updates the dialog's copy of CDataClass, the dialog would raise DataClassUpdated, and MainViewModel would have a handler for that event that sniffs at _dialogViewModel.AAAVM.CDC, and decides what to do with it. We can get into example code for that if necessary.

So now you can see what I mean by building everything in terms of parent/child viewmodels, and stuffing them into views when and as appropriate.