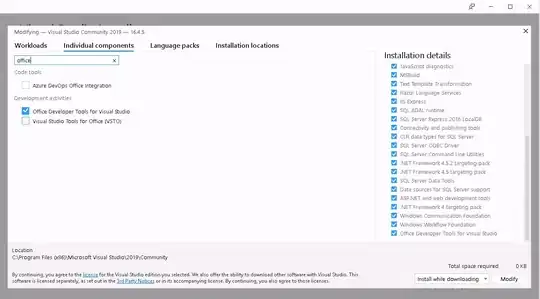

I compiled a simple program using Visual Studio 2017

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("hello, world\n");

return 0;

}

I compile it with command line

cl 1.cpp /Fa1.asm

This gives me assembly code that (mostly) makes sense to me

; Listing generated by Microsoft (R) Optimizing Compiler Version 19.14.26429.4

INCLUDELIB LIBCMT

INCLUDELIB OLDNAMES

CONST SEGMENT

$SG5542 DB 'hello, world', 0aH, 00H

CONST ENDS

PUBLIC ___local_stdio_printf_options

PUBLIC __vfprintf_l

PUBLIC _printf

PUBLIC _main

PUBLIC ?_OptionsStorage@?1??__local_stdio_printf_options@@9@4_KA ; `__local_stdio_printf_options'::`2'::_OptionsStorage

EXTRN ___acrt_iob_func:PROC

EXTRN ___stdio_common_vfprintf:PROC

; COMDAT ?_OptionsStorage@?1??__local_stdio_printf_options@@9@4_KA

_BSS SEGMENT

?_OptionsStorage@?1??__local_stdio_printf_options@@9@4_KA DQ 01H DUP (?) ; `__local_stdio_printf_options'::`2'::_OptionsStorage

_BSS ENDS

; Function compile flags: /Odtp

_TEXT SEGMENT

_main PROC

; File c:\users\mr dai\documents\michael\study\cybersecurity\reverseengineering4beg\random\random\random.cpp

; Line 3

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

; Line 4

push OFFSET $SG5542

call _printf

add esp, 4

; Line 5

xor eax, eax

; Line 6

pop ebp

ret 0

_main ENDP

_TEXT ENDS

; Function compile flags: /Odtp

; COMDAT _printf

_TEXT SEGMENT

__Result$ = -8 ; size = 4

__ArgList$ = -4 ; size = 4

__Format$ = 8 ; size = 4

_printf PROC ; COMDAT

; File c:\program files (x86)\windows kits\10\include\10.0.17134.0\ucrt\stdio.h

; Line 954

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 8

; Line 957

lea eax, DWORD PTR __Format$[ebp+4]

mov DWORD PTR __ArgList$[ebp], eax

; Line 958

mov ecx, DWORD PTR __ArgList$[ebp]

push ecx

push 0

mov edx, DWORD PTR __Format$[ebp]

push edx

push 1

call ___acrt_iob_func

add esp, 4

push eax

call __vfprintf_l

add esp, 16 ; 00000010H

mov DWORD PTR __Result$[ebp], eax

; Line 959

mov DWORD PTR __ArgList$[ebp], 0

; Line 960

mov eax, DWORD PTR __Result$[ebp]

; Line 961

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

ret 0

_printf ENDP

_TEXT ENDS

; Function compile flags: /Odtp

; COMDAT __vfprintf_l

_TEXT SEGMENT

__Stream$ = 8 ; size = 4

__Format$ = 12 ; size = 4

__Locale$ = 16 ; size = 4

__ArgList$ = 20 ; size = 4

__vfprintf_l PROC ; COMDAT

; File c:\program files (x86)\windows kits\10\include\10.0.17134.0\ucrt\stdio.h

; Line 642

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

; Line 643

mov eax, DWORD PTR __ArgList$[ebp]

push eax

mov ecx, DWORD PTR __Locale$[ebp]

push ecx

mov edx, DWORD PTR __Format$[ebp]

push edx

mov eax, DWORD PTR __Stream$[ebp]

push eax

call ___local_stdio_printf_options

mov ecx, DWORD PTR [eax+4]

push ecx

mov edx, DWORD PTR [eax]

push edx

call ___stdio_common_vfprintf

add esp, 24 ; 00000018H

; Line 644

pop ebp

ret 0

__vfprintf_l ENDP

_TEXT ENDS

; Function compile flags: /Odtp

; COMDAT ___local_stdio_printf_options

_TEXT SEGMENT

___local_stdio_printf_options PROC ; COMDAT

; File c:\program files (x86)\windows kits\10\include\10.0.17134.0\ucrt\corecrt_stdio_config.h

; Line 85

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

; Line 87

mov eax, OFFSET ?_OptionsStorage@?1??__local_stdio_printf_options@@9@4_KA ; `__local_stdio_printf_options'::`2'::_OptionsStorage

; Line 88

pop ebp

ret 0

___local_stdio_printf_options ENDP

_TEXT ENDS

END

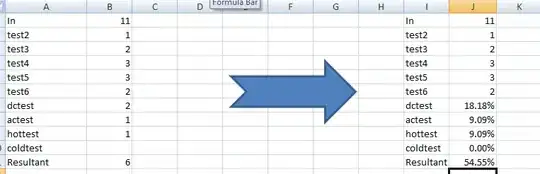

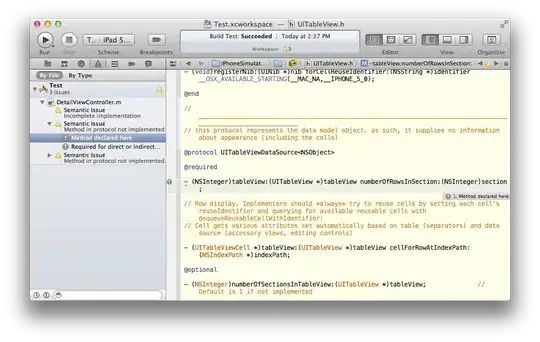

However I open the exe with IDA and the disassemble spits out something completely unintelligible.

Why is this the case? Does visual studio automatically obfuscate assembly code by default? I googled but this doesn't seem to be the case. If so, how do I turn obfuscation off?

Thanks