The problem is that there is a merge conflict, and chepner's comment is the key to understanding why. Well, that, and the commit graph, plus the fact that git rebase consists of repeated git cherry-pick operations. Interactive rebase allows you to add your own commands between each git cherry-pick, or even change the cherry-picks to something else. (The initial command-sheet starts out as all-pick commands, each of which means do a cherry-pick.)

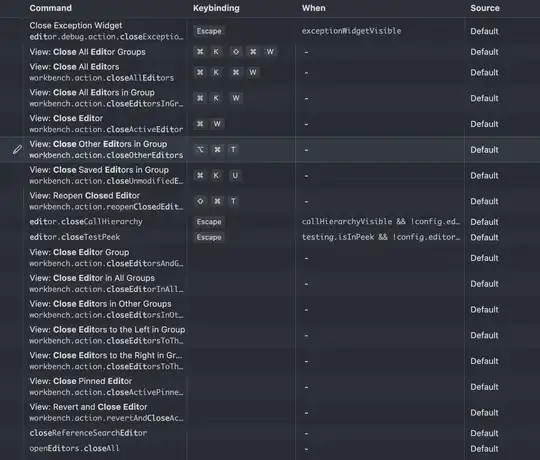

Your commit history is a summary of your commit graph—essentially, the result of visiting each commit in the commit graph, starting at some particular ending point (the tip of your current branch) and working backwards. If you use git log --graph you get some potentially-important information that is left out without --graph, although in this particular case, it's easy to see that the graph is linear. So you just have three commits:

A <-B <-C <-- master (HEAD)

where A is actually 4a5244b, B stands for 7bdb5ef, and C stands for 80384aa (if I've transcribed the images correctly). Each commit has a full, complete copy of the file names.txt. The copy is of course different in commits A, B, and C, in that in A, it's empty; in B, it is one line reading Mary; and in C, it is two lines reading Mary and then John

The graph itself arises from the fact that commit C, or 80384aa, contains the hash ID of commit B, or 7bdb5ef, inside C itself. That's why I drew an arrow coming out of C pointing to B. Git calls this C's parent commit. Git records C's hash ID in the name master, and then attaches the special name HEAD to the name master, so that it knows that this is where git log should start, and that commit C is the one you have out, for working-on, right now.

When you run git rebase -i 4a5244b—choosing commit A as the new base—Git figures out that this means copy commits B and C, so it puts their hash IDs into the list of pick commands. It then opens your editor on the command-sheet. You change pick to edit, which tells Git: Do the cherry-pick, then exit the rebase, in the middle of the operation.

You didn't force rebase to make a true copy. (To do that, use -f or --no-ff or --force-rebase—all mean the same thing. It doesn't really matter here, nor in most cases.) So Git saw that there was an instruction, Copy B so that it comes after A, and realized: Hey, wait, B is already after A. I'll just leave it there. Git did that and stopped, leaving you in this state:

A--B <-- HEAD

\

C <-- master

Note that HEAD is no longer attached to master: it now points directly to commit B. Commit C remains, and master still points to it, but Git has stopped in "detached HEAD" mode to allow you to do your edit.

You make your change to the file, git add, and git commit --amend. This makes a new commit—we could call it B' or D, and usually I use B' since usually it's a whole lot like B, but this time it's different enough, so let's use D. The new commit has A as its parent—that's what --amend does. Git updates HEAD to point to the new commit. Existing commit B remains intact. So now you have:

D <-- HEAD

/

A--B

\

C <-- master

The file names.txt in D has the new single line reading Mary Shelly.

You now run git rebase --continue, so Git continues with what's left in the instruction sheet. That consists of pick <hash-of-C>, which makes Git run git cherry-pick to copy C. This copy needs to go after the current commit, D. Existing commit C doesn't, so Git has to really do the job this time.

A cherry-pick is a merge—merge as a verb, at least

To perform a merge operation—to merge, the action—Git needs three inputs. These three inputs are the merge base commit, the current or --ours commit (also sometimes called local, particularly by git mergetool), and the other or --theirs commit (sometimes called remote). For regular merges, the base is often a bit distant: it's where the two lines of commits diverged. For cherry-pick—and for revert, for that matter—the base is right next to the commit. The merge base of this operation is C's parent commit B!

The actual operation of merge consists of running two git diff commands on the entire commits:

git diff --find-renames hash-of-base hash-of-ours: what did we change?git diff --find-renames hash-of-base hash-of-theirs: what did they change?

So Git now diffs commit B, the base, vs commit D, your current/ours commit. That diff affects file names.txt and says: change the one line that says Mary to two lines: one reading Mary Shelly, and one reading John. Then Git diffs B vs C, to see what "they" (you, earlier) did. The diff affects file names.txt and says: add the line reading John at the end of the file, after the line reading Mary.

That's what Git shows you in the merge-conflict section: one file says replace Mary with Mary Shelly, the other says keep Mary and add John. If you like, you can tell Git to keep, in the merge-conflict section, more information. To do this, set diff.conflictStyle to diff3. (The default, if it's not set, is merge.)

With the diff3 setting, you'll see that the base content—marked by |||||||—is the one line Mary, and that the two files from the conflicting commits have replaced that base with, respectively, either Mary Shelly or Mary + new line John. I find this kind of merge conflict clearer and easier to merge manually.

In any case, your job at this point is to come up with the correct result—whatever that is—and write that out and copy it into index slot zero. Typically you'll just edit the messy names.txt that Git left in your work-tree, put the right contents into it, and then run git add names.txt.

Resuming

Having fixed the conflict, run git whatever --continue to resume whatever operation stopped—in this case, rebase, but this happens with cherry-pick and merge as well. Git will use the index contents, which you updated with git add, to make the new commit that's a copy of C:

D--C' <-- HEAD

/

A--B

\

C <-- master

Having reached the end of the command sheet, git rebase now finishes up by yanking the name master off commit C and pasting it onto C', which is the last copy it made, and then re-attaching HEAD:

D--C' <-- master (HEAD)

/

A--B

\

C [abandoned]