The reason for why is because Promises are asynchronous:

logOut("start of file");

new Promise(function(accept){

accept();

}).then(function(){

logOut("inside promise");

});

function makePromise(name) {

new Promise(function(accept){

accept();

}).then(function(){

logOut("inside promise inside makePromise " + name);

});

};

logOut("value returned from makePromise: " + makePromise("one"));

try {

// just to prove this

makePromise("two").then(function(accept){

accept();

}).then(function(){

logOut("after makePromise");

});

} catch(err) {

logOut("Failed to `.then` the return value from makePromise because:\n" + err.message);

}

logOut("end of file");

var outputList;

function logOut(str){

outputList = outputList || document.getElementById("output");

outputList.insertAdjacentHTML("beforeend", "<li><pre>" + str + "</pre></li>");

}

<ol id="output"></ol>

As seen above, the whole program does not pause for the .then statement. That is why they are called Promises: because the rest of the code goes on while the Promise is waiting to be resolved. Further, as seen above, there can be a value returned from a function only if the function explicitly returns the value via the then keyword. JavaScript functions do not automatically return the value of the last executed statement.

Please see my website here for more info on Promises.

In the demo below, I have attempted to fix up the fragments of the files you slapped on this question. Then, I proceeded to wrap them together into a quick single-file system I typed up

(function(){"use strict";

// NOTE: This setup code makes no attempt to accurately replicate the

// NodeJS api. This setup code only tries to concisely mimics

// the NodeJS API solely for the purposes of preserving your code

// in its present NodeJS form.

var modules = {}, require = function(fileName){return modules[fileName]};

for (var i=0; i < arguments.length; i=i+1|0)

arguments[i]({exports: modules[arguments[i].name] = {}}, require);

})(function https(module, require){"use strict";

////////////// https.js //////////////

module.exports.request = function(options, withWrapper) {

var p, when = {}, wrapper = {on: function(name, handle){

when[name] = handle;

}, end: setTimeout.bind(null, function(){

if (p === "/api/getOne/world") when.data("HTTP bar in one 1");

else if (p === "/api/getTwo/foo") when.data("HTTP foo in two 2");

else {console.error("Not stored path: '" + p + "'");

return setTimeout(when.error);}

setTimeout(when.end); // setTimeout used for asynchrony

}, 10 + Math.random()*30)}; // simulate random http delay

setTimeout(withWrapper, 0, wrapper); // almost setImmediate

return p = options.path, options = null, wrapper;

};

/******* IGNORE ALL CODE ABOVE THIS LINE *******/

}, function myModule(module, require) {"use strict";

////////////// myModule.js //////////////

const HttpsModule = require('https');

module.exports.getApiOne = function(value) {

var params = {path: '/api/getOne/' + value};

// There is no reason for `.then(response => response);`!

// It does absolutely nothing.

return getApi(params); // .then(response => response);

};

module.exports.getApiTwo = function(value) {

var params = {path: '/api/getTwo/' + value};

return getApi(params); // .then(response => response);

};

function getApi(params) {

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

var req = HttpsModule.request(params, function(res) {

var body = [];

res.on('data', function(chunk) {

body.push(chunk);

});

res.on('end', function() {

try {

body = body.join("");//Buffer.concat(body).toString();

} catch (e) {

reject(e);

}

resolve(body);

});

});

req.on('error', function(err) {

reject(err);

});

req.end();

});

}

}, function main(module, require) {"use strict";

////////////// top JS script //////////////

const MyStatusModule = require('myModule');

const isPromise = isPrototypeOf.bind(Promise.prototype)

var someObject = {};

function someFunction(inputObject) {

// initialize object

// NOTE: Javascript IS case-sensitive, so `.Id` !== `.id`

if (!someObject.hasOwnProperty(inputObject.id)) {

someObject[inputObject.id] = {};

someObject[inputObject.id].contact = {};

}

// get object

var objectForThis = someObject[inputObject.id];

switch (inputObject.someValue) {

case 'test':

//... some code

return objectForThis.stage = 'test';

break;

case 'hello':

return MyStatusModule.getApiOne('world').then(function (response) {

// console.log(response);

return objectForThis.stage = 'zero'

});

break;

default:

return someOtherFunction(objectForThis.stage).then(function (response) {

return objectForThis.stage = response;

});

break;

}

}

function someOtherFunction(stage) {

var newStage;

// If you return nothing, then you would be calling `.then` on

// on `undefined` (`undefined` is the default return value).

// This would throw an error.

return new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

switch (stage) {

case 'zero':

// some code

newStage = 'one';

resolve(newStage); // you must call `resolve`

case 'one':

return MyStatusModule.getApiTwo('foo').then(function (response) {

// console.log(response);

newStage = 'two';

/********************************************

I assume, the problem lies here, it's

'resolving' (below) before this sets the new

value for 'newStage'

********************************************/

resolve(newStage); // you must call `resolve`

});

break;

default:

// do nothing

resolve(newStage); // you must call `resolve`

break;

}

});

}

// tests:

function logPromise(){

var a=arguments, input = a[a.length-1|0];

if (isPromise(input)) {

for (var c=[null], i=0; i<(a.length-1|0); i=i+1|0) c.push(a[i]);

return input.then(logPromise.bind.apply(logPromise, c));

} else console.log.apply(console, arguments);

}

logPromise("test->test: ", someFunction({id: 1, someValue: 'test'})); // sets 'stage' to 'test'

logPromise("hello->zero: ", someFunction({id: 1, someValue: 'hello'})) // sets 'stage' to 'zero'

.finally(function(){ // `.finally` is like `.then` without arguments

// This `.finally` waits until the HTTP request is done

logPromise("foo->one: ", someFunction({id: 1, someValue: 'foo'})) // sets 'stage' to 'one'

.finally(function(){

debugger;

logPromise("bar->two: ", someFunction({id: 1, someValue: 'bar'})); // NOT setting 'stage' to 'two'

});

});

});

If it is not apparent already, do not copy the above snippet into your code. It will break your code because the above snippet is rigged with dummy Node modules designed to produce set results. Instead, copy each individual file (each wrapped in a function) from the snippet above into the corresponding file of your code if you must copy. Also, while copying, keep in mind not to copy the dummy stuff above the blatant IGNORE ALL CODE ABOVE THIS LINE indicator. Also, do not forget to test rigorously. I am much more familiar with browser JavaScript than Node JavaScript, so it is possible (though unlikely) that I may have introduced a potential source of errors.

someObject[inputObject.id] = objectForThis; is not needed

I could give you a super concise quick answer to this question. However, I feel that the "quick" answer would not do you justice because this particular question requires a far greater depth of understanding to be able come up with an explanation than to simply read someone else's explanation. Further, this is a very crucial concept in Javascript. Thus, it is very necessary to be able to come up with the explanation on your own so that you do not run into the same trouble again 5 minutes from now. Thus I have written the below tutorial to guide you to the answer so that you can be sure that you have complete understanding.

In Javascript, there are expressions such as 7 - 4 which yields 3. Each expression returns a value that may be used by further expressions. 3 * (4 + 1) first evaluates 4 + 1 into 3 * 5, then that yields 15. Assignment expressions (=,+=,-=,*=,/=,%=,**=,&=,|=, and ^=) only change the left-hand variable. Any right-hand variable stays the exact same and contains the same value:

var p = {};

var ptr = p;

// Checkpoint A:

console.log('Checkpoint A: p === ptr is now ' + (p === ptr));

ptr = null;

// Checkpoint B:

console.log('Checkpoint B: p === ptr is now ' + (p === ptr));

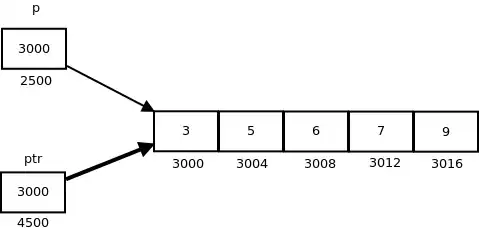

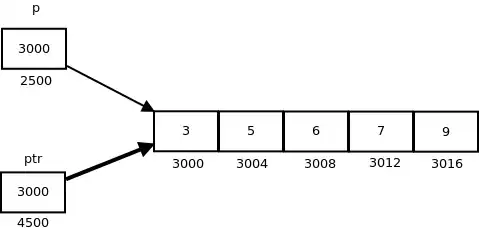

Let us examine what p and ptr look like at Checkpoint A.

As seen in the above diagram, both p and ptr are kept separate even though they both point to the same object. Thus, at Checkpoint B, changing ptr to a different value does not change p to a different value. At Checkpoint B, variable p has remained unchanged while ptr is now null.

At Checkpoint A, keep in mind that (although p and ptr are distinct variables with different memory addresses) p and ptr both point to the same object because the location in memory they point to is the same index number. Thus, if we changed this object at checkpoint A, then reading/writing the properties of p would be the same as reading/writing the properties of ptr because you are changing the data being pointed to, not which variable is pointing to what data.

function visualize(inputObject) {

// displays an object as a human-readable JSON string

return JSON.stringify(inputObject);

}

var p = {};

p.hello = "world";

// Checkpoint 0:

console.log('Checkpoint 0: p is ' + visualize(p));

var ptr = p;

ptr.foo = "bar";

// Checkpoint A:

console.log('Checkpoint A: p is ' + visualize(p) + ' while ptr is ' + visualize(ptr));

ptr = null;

// Checkpoint B:

console.log('Checkpoint B: p is ' + visualize(p) + ' while ptr is ' + visualize(ptr));

p.foo = p.hello;

// Checkpoint C:

console.log('Checkpoint C: p is ' + visualize(p) + ' while ptr is ' + visualize(ptr));

As seen at Checkpoint A above, changing p is the same as changing ptr. What about when we reassign an object? The old object which is no longer pointed to get cleaned up by tan automatic Garbage Collector.

function visualize(inputObject) {

// displays an object as a human-readable JSON string

return JSON.stringify(inputObject);

}

var first = {one: "is first"};

first = {uno: "es el primero"};

var second = {two: "is second"};

second = first;

console.log("second is " + JSON.stringify(second));

Function arguments are the same as variables in this respect.

var obj = {};

setVariable(obj);

obj.key = "value";

console.log("obj is " + JSON.stringify(obj));

function setVariable(inputVariable){

inputVariable.setValue = "set variable value";

inputVariable = null;

}

Is the same as:

var obj = {};

/*function setVariable(*/ var inputVariable = obj; /*){*/

inputVariable.setValue = "set variable value";

inputVariable = null;

/*}*/

obj.key = "value";

console.log("obj is " + JSON.stringify(obj));

Objects are also no different:

function visualize(inputObject) {

// displays an object as a human-readable JSON string

return JSON.stringify(inputObject);

}

var variables = {};

var aliasVars = variables;

// Now, `variables` points to the same object as `aliasVars`

variables.p = {};

aliasVars.p.hello = "world";

// Checkpoint 0:

console.log('Checkpoint 0: variables are ' + visualize(variables));

console.log('Checkpoint 0: aliasVars are ' + visualize(aliasVars));

variables.ptr = aliasVars.p;

aliasVars.ptr.foo = "bar";

// Checkpoint A:

console.log('Checkpoint A: variables are ' + visualize(variables));

console.log('Checkpoint A: aliasVars are ' + visualize(aliasVars));

variables.ptr = null;

// Checkpoint B:

console.log('Checkpoint B: variables are ' + visualize(variables));

console.log('Checkpoint B: aliasVars are ' + visualize(aliasVars));

aliasVars.p.foo = variables.p.hello;

// Checkpoint C:

console.log('Checkpoint C: variables are ' + visualize(variables));

console.log('Checkpoint C: aliasVars are ' + visualize(aliasVars));

Next is object notation just to make sure that we are on the same page.

var obj = {};

obj.one = 1;

obj.two = 2;

console.log( "obj is " + JSON.stringify(obj) );

is the same as

var obj = {one: 1, two: 2};

console.log( "obj is " + JSON.stringify(obj) );

is the same as

console.log( "obj is " + JSON.stringify({one: 1, two: 2}) );

is the same as

console.log( "obj is {\"one\":1,\"two\":2}" );

The hasOwnProperty allows us to determine whether or not an object has a property.

var obj = {};

// Checkpoint A:

console.log("Checkpoint A: obj.hasOwnProperty(\"hello\") is " + obj.hasOwnProperty("hello"));

console.log("Checkpoint A: obj[\"hello\"] is " + obj["hello"]);

obj.hello = "world"; // now set the variable

// Checkpoint B:

console.log("Checkpoint B: obj.hasOwnProperty(\"hello\") is " + obj.hasOwnProperty("hello"));

console.log("Checkpoint B: obj[\"hello\"] is " + obj["hello"]);

obj.hello = undefined;

// Checkpoint C:

console.log("Checkpoint C: obj.hasOwnProperty(\"hello\") is " + obj.hasOwnProperty("hello"));

console.log("Checkpoint C: obj[\"hello\"] is " + obj["hello"]);

delete obj.hello;

// Checkpoint D:

console.log("Checkpoint D: obj.hasOwnProperty(\"hello\") is " + obj.hasOwnProperty("hello"));

console.log("Checkpoint D: obj[\"hello\"] is " + obj["hello"]);

Prototypes in javascript are crucial to understanding hasOwnProperty and work as follows: when a property is not found in an object, the object's __proto__ is checked for the object. When the object's __proto__ does not have the property, the object's __proto__'s __proto__ is checked for the property. Only after an object without a __proto__ is reached does the browser assume that the wanted property does not exist. The __proto__ is visualized below.

var obj = {};

console.log('A: obj.hasOwnProperty("foo") is ' + obj.hasOwnProperty("foo"));

console.log('A: obj.foo is ' + obj.foo);

obj.__proto__ = {

foo: 'value first'

};

console.log('B: obj.hasOwnProperty("foo") is ' + obj.hasOwnProperty("foo"));

console.log('B: obj.foo is ' + obj.foo);

obj.foo = 'value second';

console.log('C: obj.hasOwnProperty("foo") is ' + obj.hasOwnProperty("foo"));

console.log('C: obj.foo is ' + obj.foo);

delete obj.foo;

console.log('D: obj.hasOwnProperty("foo") is ' + obj.hasOwnProperty("foo"));

console.log('D: obj.foo is ' + obj.foo);

delete obj.__proto__.foo;

console.log('E: obj.hasOwnProperty("foo") is ' + obj.hasOwnProperty("foo"));

console.log('E: obj.foo is ' + obj.foo);

Infact, we could even store a reference to the __proto__ and share this reference between objects.

var dog = {noise: "barks"};

var cat = {noise: "meow"};

var mammal = {animal: true};

dog.__proto__ = mammal;

cat.__proto__ = mammal;

console.log("dog.noise is " + dog.noise);

console.log("dog.animal is " + dog.animal);

dog.wagsTail = true;

cat.clawsSofa = true;

mammal.domesticated = true;

console.log("dog.wagsTail is " + dog.wagsTail);

console.log("dog.clawsSofa is " + dog.clawsSofa);

console.log("dog.domesticated is " + dog.domesticated);

console.log("cat.wagsTail is " + cat.wagsTail);

console.log("cat.clawsSofa is " + cat.clawsSofa);

console.log("cat.domesticated is " + cat.domesticated);

However, the above syntax is terribly illperformant because it is bad to change the __proto__ after the object has been created. Thus, the solution is to set the __proto__ along with the creation of the object. This is called a constructor.

function Mammal(){}

// Notice how Mammal is a function, so you must do Mammal.prototype

Mammal.prototype.animal = true;

var dog = new Mammal();

// Notice how dog is an instance object of Mammal, so do NOT do dog.prototype

dog.noise = "bark";

var cat = new Mammal();

cat.noise = "meow";

console.log("dog.__proto__ is Mammal is " + (dog.__proto__===Mammal));

console.log("cat.__proto__ is Mammal is " + (cat.__proto__===Mammal));

console.log("dog.__proto__ is Mammal.prototype is " + (dog.__proto__===Mammal.prototype));

console.log("cat.__proto__ is Mammal.prototype is " + (cat.__proto__===Mammal.prototype));

console.log("dog.noise is " + dog.noise);

console.log("dog.animal is " + dog.animal);

dog.wagsTail = true;

cat.clawsSofa = true;

Mammal.prototype.domesticated = true;

console.log("dog.wagsTail is " + dog.wagsTail);

console.log("dog.clawsSofa is " + dog.clawsSofa);

console.log("dog.domesticated is " + dog.domesticated);

console.log("cat.wagsTail is " + cat.wagsTail);

console.log("cat.clawsSofa is " + cat.clawsSofa);

console.log("cat.domesticated is " + cat.domesticated);

Next, the this object in Javascript is not a reference to the instance like in Java. Rather, the this in Javascript refers to the object in the expression object.property() when functions are called this way. When functions are not called this way, the this object refers to undefined in strict mode or window in loose mode.

"use strict"; // "use strict"; at the VERY top of the file ensures strict mode

function logThis(title){

console.log(title + "`this === undefined` as " + (this === undefined));

if (this !== undefined) console.log(title + "`this.example_random_name` as " + this.example_random_name);

}

logThis.example_random_name = "log this raw function";

logThis("logThis() has ");

var wrapper = {logThis: logThis, example_random_name: "wrapper around logThis"};

wrapper.logThis("wrapper.logThis has ");

var outer = {wrapper: wrapper, example_random_name: "outer wrap arounde"};

outer.wrapper.logThis("outer.wrapper.logThis has ");

We can finally take all this knowledge and extrapolate it out to the real example.

var someObject = {};

function someFunction(inputObject) {

if (!someObject.hasOwnProperty(inputObject.id)) {

someObject[inputObject.id] = {};

someObject[inputObject.id].contact = {};

}

// get object

var objectForThis = someObject[inputObject.id];

objectForThis.stage = inputObject.stage;

}

var setTo = {};

setTo.id = 1;

setTo.stage = "first stage";

someFunction(setTo);

console.log("someObject is " + JSON.stringify(someObject));

First, let us inline the function and the setTo

var someObject = {};

var setTo = {id: 1, stage: "first stage"};

/*function someFunction(*/ var inputObject = setTo; /*) {*/

if (!someObject.hasOwnProperty(inputObject.id)) {

someObject[inputObject.id] = {};

someObject[inputObject.id].contact = {};

}

// get object

var objectForThis = someObject[inputObject.id];

objectForThis.stage = inputObject.stage;

/*}*/

console.log("someObject is " + JSON.stringify(someObject));

Next, let us inline the setTo object.

var someObject = {};

var setTo = {id: 1, stage: "first stage"};

if (!someObject.hasOwnProperty(setTo.id)) {

someObject[setTo.id] = {};

someObject[setTo.id].contact = {};

}

// get object

var objectForThis = someObject[setTo.id];

objectForThis.stage = setTo.stage;

console.log("someObject is " + JSON.stringify(someObject));

Then:

var someObject = {};

if (!someObject.hasOwnProperty(1)) {

someObject[1] = {};

someObject[1].contact = {};

}

// get object

var objectForThis = someObject[1];

objectForThis.stage = "first stage";

console.log("someObject is " + JSON.stringify(someObject));

To visually demonstrate the pointers:

var someObject = {};

if (!someObject.hasOwnProperty(1)) {

var createdObject = {};

someObject[1] = createdObject;

someObject[1].contact = {};

}

// get object

var objectForThis = someObject[1];

console.log("createdObject === objectForThis is " + (createdObject === objectForThis));

objectForThis.stage = "first stage";

console.log("someObject is " + JSON.stringify(someObject));

Please tell me if you have any further questions.

If you are just glancing at this, then please don't forget to read the full article above. I promise you that my article above is shorter and tries to go deeper into Javascript than any other article you may find elsewhere on the internet.