If you know about C and pointers, you can picture nums as a pointer to a list.

Consider this case:

def reverse(nums):

nums = nums[::-1]

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

reverse(my_list)

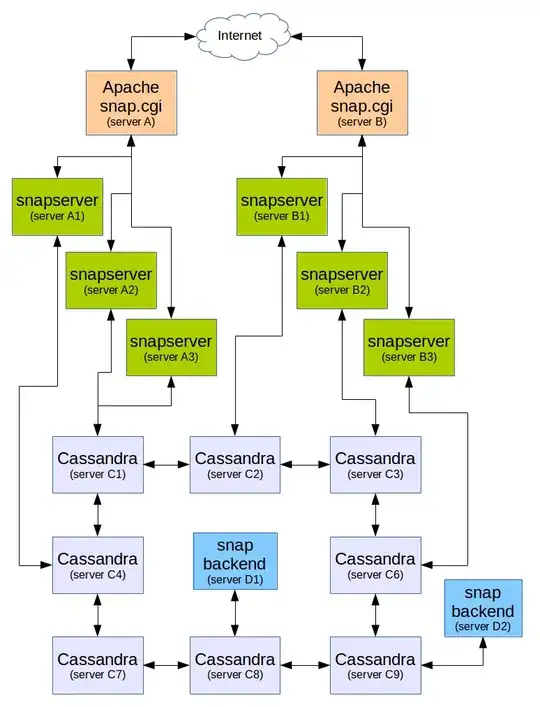

The assignment nums = nums[::-1] would be equivalent to create a new list in memory (with the elements reversed), and changing the pointer nums to point to that new list. But since the variable nums that you change is local to the function, this change does not affect to the external one passed as parameter, as shown in this picture:

Now consider this case:

def reverse(nums):

nums[:] = nums[::-1]

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

reverse(my_list)

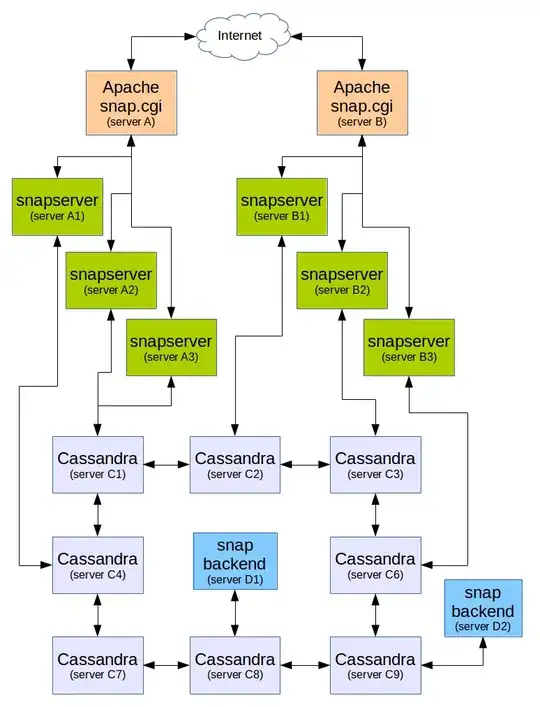

The assignment nums[:] = nums[::-1] would be equivalent to write a new reversed list at the same address pointed by nums, because the slice allows to replace part of a list with new contents (although in this case the "part" is the whole list).

In this case you are not changing the variable nums, but the data pointed by it. This is shown in the following picture:

Note that in fact all variables in python are "pointer" in the sense used in this answer, but only lists and dicts allow to replace "in-place" some contents (they are mutable data types). With any other type (inmutable) you cannot alter the data in memory, so all you can do is to "reassign the pointer" as in the first case, and this is the reason why a function cannot change the data received as parameter, except for the list case.