Suppose I say A..B. From here

The most common range specification is the double-dot syntax. This basically asks Git to resolve a range of commits that are reachable from one commit but aren’t reachable from another.

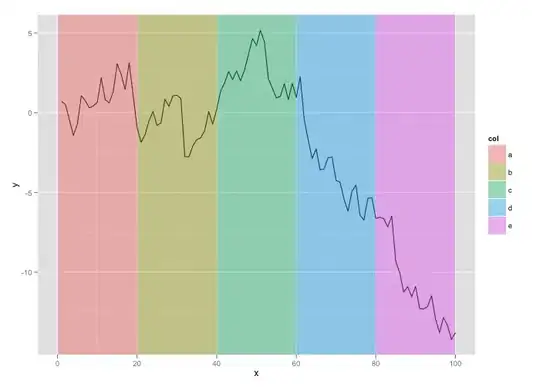

Let us say, a graph like this:

* c6ddc03 (HEAD -> topic) t6

* 11751b7 t5

* a1c4ed2 Merge branch 'small_topic1' into topic

|\

| * 7bc86ff s2

| * e1b1384 s1

* | 9582f60 t4

* | 815137a t3

|/

* 648741c t2

* cfce615 t1

| * 7e46c48 (master) m2

| * 84a4dc7 m3

|/

* 2d15aa1 1

If I say what is 7bc86ff..c6ddc03 , then I get

c6ddc037e9e67647ae69e213c0c5b8a29f5d2745

11751b72f943c4daeb9f28a8dddd93a4b98cb8dc

a1c4ed284557cde1e1474bc5e3f7ef0cd7008ba8

9582f60bf9e5464254a51cb6a085d41005f5795f

815137ac9cbe51768cdaf4c27200f51ecad27fbb

Clearly, this tells us that A..B does not take merge-base (which is 7bc86ff in figure above) into consideration.

Because if we had defined A..B as - All commits of B from merge-base of A and B , then this definition wont give above answer.

My question is when we say git rebase --fork-point A B uses fork-point to evaluate A..B, then is not it wrong ? When even merge-base does not effect A..B selection , how can fork-point be used for it ?

For those who want above commit graph in local, run this script

#!/bin/bash

git init .

echo "10" >> 1.txt && git add . && git commit -m "1"

# Add 2 commits to master

echo "3" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "m3"

echo "2" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "m2"

#checkout topic branch

git checkout -b topic HEAD~2

echo "1" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "t1"

echo "2" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "t2"

echo "1" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "t3"

echo "2" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "t4"

#checkout small_topic

git checkout -b small_topic1 HEAD~2

echo "1" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "s1"

echo "2" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "s2"

git checkout topic

git merge small_topic1

echo "1" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "t5"

echo "2" >> 1.txt && git commit -am "t6"

git branch -D small_topic1

#Show graph

git log --oneline --all --decorate --graph