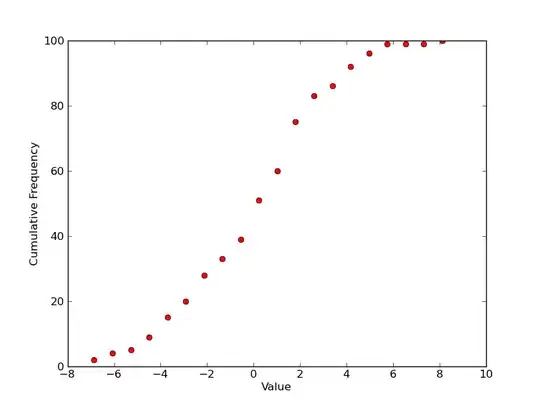

I am computing the dFT of a function f(x) sampled at x_i, i=0,1,...,N (with a known dx) at the frequencies u_j, j=0,1,...,N where u_j are frequencies that np.fft.fftfreq(N, dx) generates and compare it with the result of np.fft.fft(f(x)). I find that the two do not agree...

Am I missing something? Shouldn't they by definition be the same? (The difference is even worse when I am looking at the imag parts of the dFT/FFT).

I am attaching the script that I used, which generates this plot that compares the real and imag parts of the dFT and FFT.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from astropy import units

def func_1D(x, sigma_x):

return np.exp(-(x**2.0 / (2.0 * sigma_x**2)))

n_pixels = int(2**5.0)

pixel_scale = 0.05 # units of arcsec

x_rad = np.linspace(

-n_pixels * pixel_scale / 2.0 * (units.arcsec).to(units.rad) + pixel_scale / 2.0 * (units.arcsec).to(units.rad),

+n_pixels * pixel_scale / 2.0 * (units.arcsec).to(units.rad) - pixel_scale / 2.0 * (units.arcsec).to(units.rad),

n_pixels)

sigma_x = 0.5 # in units of arcsec

image = func_1D(

x=x_rad,

sigma_x=sigma_x * units.arcsec.to(units.rad),

)

image_FFT = np.fft.fftshift(np.fft.fft(np.fft.fftshift(image)))

u_grid = np.fft.fftshift(np.fft.fftfreq(n_pixels, d=pixel_scale * units.arcsec.to(units.rad)))

image_dFT = np.zeros(shape=n_pixels, dtype="complex")

for i in range(u_grid.shape[0]):

for j in range(n_pixels):

image_dFT[i] += image[j] * np.exp(

-2.0

* np.pi

* 1j

* (u_grid[i] * x_rad[j])

)

value = 0.23

figure, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1,ncols=3,figsize=(14,6))

axes[0].plot(x_rad * 10**6.0, image, marker="o")

for x_i in x_rad:

axes[0].axvline(x_i * 10**6.0, linestyle="--", color="black")

axes[0].set_xlabel(r"x ($\times 10^6$; rad)")

axes[0].set_title("x-plane")

for u_grid_i in u_grid:

axes[1].axvline(u_grid_i / 10**6.0, linestyle="--", color="black")

axes[1].plot(u_grid / 10**6.0, image_FFT.real, color="b")

axes[1].plot(u_grid / 10**6.0, image_dFT.real, color="r", linestyle="None", marker="o")

axes[1].set_title("u-plane (real)")

axes[1].set_xlabel(r"u ($\times 10^{-6}$; rad$^{-1}$)")

axes[1].plot(u_grid / 10**6.0, image_FFT.real - image_dFT.real, color="black", label="difference")

axes[2].plot(u_grid / 10**6.0, image_FFT.imag, color="b")

axes[2].plot(u_grid / 10**6.0, image_dFT.imag, color="r", linestyle="None", marker="o")

axes[2].set_title("u-plane (imag)")

axes[2].set_xlabel(r"u ($\times 10^{-6}$; rad$^{-1}$)")

#axes[2].plot(u_grid / 10**6.0, image_FFT.imag - image_dFT.imag, color="black", label="difference")

axes[1].legend()

plt.show()