tl;dr

When a method ends, the local variable is cleared.

Technically, all local items added (“pushed”) to the stack during a method call are automatically cleared (“popped”) from the stack as the method ends/returns.

If a local variable is returned by a method, a copy of the content of that variable is what actually gets sent back to the calling method.

Details

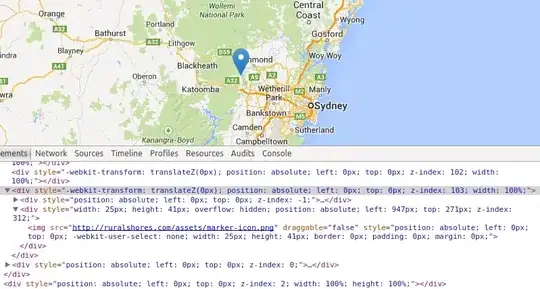

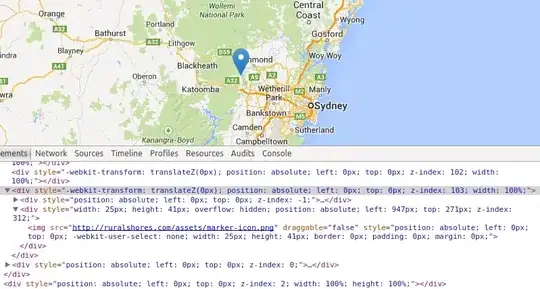

Here is a diagram of your example, with feline name changes to make matters more concrete (pun intended).

First thing you do is establish a reference variable named fluffy that is intended to hold a reference to a Cat object. That variable by default holds no reference, holding nothing at all until later when a reference might eventually be assigned. We call that state null, pointing to no object at all.

Then you make a call to the static method Cat.makeCat. Upon executing the makeCat() part, flow-of-control jumps to the other method.

When executing new Cat(), you are doing two things:

- Instantiating an object, that is, grabbing a piece of memory (in the heap) that has bytes ready to hold the various fields defined by the class. The class is like a cookie-cutter, and each instance (each object) is like a cookie cut from memory in place of dough.

- Capturing a reference to that object, that is, remembering the location in memory where that object lives.

The reference (pointer) is the return value from your call to new Cat(). That reference is stored in your local variable c (on the stack).

Then you call return c. That sends a xerox copy of the reference (the address in memory) back to the calling method. The stack pops the items held for that method call, so the reference held in variable named c is cleared, poof!, gone.

The flow-of-control, along with that copy of the reference, returns back to the calling method named main. The copy of the reference is placed in a local variable named fluffy (on the stack).

➥ Regarding the main point of your Question: The local variable c lived and died, while its contents were copied by the returns statement to the calling method.

Your app then ends, exiting at the end of the main method. Again the stack pops the items for that method call, and the fluffy variable and its contents are cleared, poof!, gone. The Cat object we instantiated is still floating around in memory. That Cat object is now a candidate for garbage collection, eventually to be cleared from memory, and that memory free to be reassigned to some other use such as holding a new object. Of course, all of this paragraph is moot, as app is exiting and the JVM shutting down, and all related memory is cleared.

The local variables fluffy and c eventually end up both pointing to the same object in memory, each variable technically holding the equivalent of the memory address of that single Cat object.

These concepts of pointers/references with a memory address, stack and heap, and returning by reference versus returning by value, are tricky to get at first, quite abstract and fuzzy. Eventually, if you keep at it, the concepts pop into place, becoming amazingly clear and simple. Until then, keep on coding. In day-to-day work, Java programmers do not consciously reflect on these concepts. We just think of fluffy and c as holding a cat, with the cat being passed around from method to method, though that is not technically accurate.