Let's start off by looking at the anatomy of an init property.

Take these two simple examples:

public class Foo

{

public string Name { get; set; }

}

public class Bar

{

public string Name { get; init; }

}

Let's look at the IL differences between the two:

.class nested public auto ansi beforefieldinit Foo extends [System.Runtime]System.Object

{

.method public hidebysig specialname instance string get_Name () cil managed { ... }

.method public hidebysig specialname instance void set_Name (string 'value') cil managed { ... }

.property instance string Name()

{

.get instance string Foo::get_Name()

.set instance void Foo::set_Name(string)

}

}

.class nested public auto ansi beforefieldinit Bar extends [System.Runtime]System.Object

{

.method public hidebysig specialname instance string get_Name () cil managed { ... }

.method public hidebysig specialname instance void modreq([System.Runtime]System.Runtime.CompilerServices.IsExternalInit) set_Name (string 'value') cil managed { ... }

.property instance string Name()

{

.get instance string Bar::get_Name()

.set instance void modreq([System.Runtime]System.Runtime.CompilerServices.IsExternalInit) Bar::set_Name(string)

}

}

The only difference between the two is the modreq([System.Runtime]System.Runtime.CompilerServices.IsExternalInit).

Both Foo and Bar implement a public getter & setter, just that Bar has a special IsExternalInit attribute on the public setter.

The difference is compiler controlled. The only time that an init property can be set is during construction or within the object initializer.

Let's look at a more complicated example:

public class Electricity

{

private const double _amps = 4.2;

public double Amps => _amps;

private readonly double _power;

public double Power => _power;

private double _volts;

public double Volts

{

get => _volts;

init

{

_volts = value * 2;

_power = value * _amps;

//_amps = 99.0; // Not allowed! Can only be set by direct assignment - effectively prior to construction!

}

}

public Electricity(double volts)

{

this.Volts = volts * 5;

_power = 9.2;

//_amps = 42.0; // Not allowed! Can only be set by direct assignment - effectively prior to construction!

}

public void Danger()

{

//_amps = 0.0; // Not allowed! Can only be set by direct assignment - effectively prior to construction!

//_power = 0.0; // Not allowed! Can only be set in constructor or init

//this.Volts = -1.0; // Not allowed! Can only be set in constructor or init

_volts = 0.0; // Allowed!

}

}

With this, I can create an instance with this code:

Electricity e = new Electricity(1.0) { Volts = 2.0 };

Now this effectively calls new Electricity(1.0) to create the instance of the class, and, since it is the only constructor, I am forced to call it with a parameter for volts. Note that, inside the constructor, I can call this.Volts = volts * 5;.

Before the assignment to e the code in the initializer block is called. It's just assigning 2.0 to Volts - it is the direct equivalent of e.Volts = 2.0; had we not declared Volts with an init setter.

The result is that by the time e gets assigned the constructor and the call to set Volts have both completed.

Now let's try to make this Electricity code more robust. Let's say that I wanted to be able to set any two properties and have the code compute the third.

A naïve and incorrect implementation would be this:

public class Electricity

{

public double Volts { get; private set; }

public double Amps { get; private set; }

public double Watts => this.Volts * this.Amps;

public Electricity(double volts, double amps)

{

this.Volts = volts;

this.Amps = amps;

}

public Electricity(double volts, double watts)

{

this.Volts = volts;

this.Amps = watts / this.Volts;

}

public Electricity(double amps, double watts)

{

this.Amps = amps;

this.Volts = watts / this.Amps;

}

}

But, of course, this doesn't compile because the three constructors signatures are the same.

But we can use init to make an object that works no matter what properties I set (with the exception of Watts in the example below).

public class Electricity

{

private readonly double? _volts = null;

private readonly double? _amps = null;

private readonly double? _watts = null;

public double Volts

{

get => _volts ?? 0.0;

init

{

_volts = value;

if (_amps.HasValue)

{

_watts = _volts * _amps;

}

else if (_watts.HasValue)

{

_amps = _watts / _volts;

}

}

}

public double Amps

{

get => _amps ?? 0.0;

init

{

_amps = value;

if (_volts.HasValue)

{

_watts = _volts * _amps;

}

else if (_watts.HasValue)

{

_volts = _watts / _amps;

}

}

}

public double Watts

{

get => _watts ?? 0.0;

init

{

_watts = value;

if (_volts.HasValue)

{

_amps = _watts / _volts;

}

else if (_amps.HasValue)

{

_volts = _watts / _amps;

}

}

}

}

I can now do this:

var electricities = new[]

{

new Electricity() { Amps = 2.0, Volts = 3.0 },

new Electricity() { Watts = 2.0, Volts = 3.0 },

new Electricity() { Amps = 2.0, Watts = 3.0 },

new Electricity(),

};

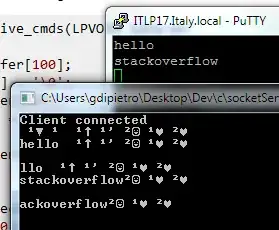

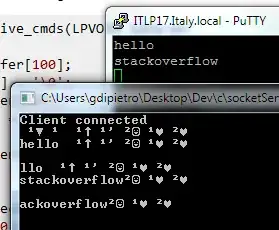

This gives me:

So, the net result is that constructors are compulsory, but init properties are optional yet must be used at the time of construction before any reference is passed back to the calling code.