I know of some people who use git pull --rebase by default and others who insist never to use it. I believe I understand the difference between merging and rebasing, but I'm trying to put this in the context of git pull. Is it just about not wanting to see lots of merge commit messages, or are there other issues?

- 12,111

- 21

- 91

- 136

- 192,085

- 135

- 376

- 510

-

9Source for people advising against git **pull** --rebase? Rebase or git rebase is **separate** activity from git **pull** --rebase! – przemo_li Apr 17 '18 at 12:49

11 Answers

I would like to provide a different perspective on what git pull --rebase actually means, because it seems to get lost sometimes.

If you've ever used Subversion (or CVS), you may be used to the behavior of svn update. If you have changes to commit and the commit fails because changes have been made upstream, you svn update. Subversion proceeds by merging upstream changes with yours, potentially resulting in conflicts.

What Subversion just did, was essentially git pull --rebase. The act of re-formulating your local changes to be relative to the newer version is the "rebasing" part of it. If you had done svn diff prior to the failed commit attempt, and compare the resulting diff with the output of svn diff afterwards, the difference between the two diffs is what the rebasing operation did.

The major difference between Git and Subversion in this case is that in Subversion, "your" changes only exist as non-committed changes in your working copy, while in Git you have actual commits locally. In other words, in Git you have forked the history; your history and the upstream history has diverged, but you have a common ancestor.

In my opinion, in the normal case of having your local branch simply reflecting the upstream branch and doing continuous development on it, the right thing to do is always --rebase, because that is what you are semantically actually doing. You and others are hacking away at the intended linear history of a branch. The fact that someone else happened to push slightly prior to your attempted push is irrelevant, and it seems counter-productive for each such accident of timing to result in merges in the history.

If you actually feel the need for something to be a branch for whatever reason, that is a different concern in my opinion. But unless you have a specific and active desire to represent your changes in the form of a merge, the default behavior should, in my opinion, be git pull --rebase.

Please consider other people that need to observe and understand the history of your project. Do you want the history littered with hundreds of merges all over the place, or do you want only the select few merges that represent real merges of intentional divergent development efforts?

- 17,291

- 7

- 48

- 81

- 9,917

- 2

- 16

- 5

-

29@MarceloCantos To be clear, I am not saying that git (the tool) should default to rebase. That would be dangerous since a rebase essentially destroys history. I am saying that in terms of workflow, when you are not intending to branch and are just hacking away at some branch that other people are also working on, "git pull --rebase" should be the default behavior of the user. – scode Oct 01 '11 at 08:12

-

1Are you saying that one shouldn't `git config --global branch.autosetupmerge always`? – Marcelo Cantos Oct 01 '11 at 14:30

-

12@MarceloCantos No I'm not ;) Personally I would leave autosetupmerge ast the default of true (if I'm merging back and fourth between branches other than local<->remote, I like it to be explicit). I am just saying that as a human, I always use "git pull --rebase" as part of my normal "grab latest in master branch" workflow, because I never want to create a merge commit unless I am explicitly branching. – scode Oct 02 '11 at 10:58

-

1

-

17+1 @scode. After many painful hours of grappling with the rebase/merge question, *finally* here's an answer that nails it. – Thinkisto Oct 16 '12 at 05:55

-

15This answer is just an attempt to adapt non-distributed version control systems users to Git instead of giving them a chance to properly understand the benefits of having proper branches. – Alexey Zimarev Sep 23 '13 at 07:51

-

3Awesome! I work in a company where the strategy is cherry-pick not merge nor pull request, therefore the local branch must reflect the remote and we should always "update" the local branch before pushing to avoid conflicts in the code-review tool. I always use `git fetch && git rebase` explicitly, does it do the same thing as `git pull --rebase`? – Thomas H. Apr 09 '19 at 20:27

-

As for 'since a rebase essentially destroys history' I feel a pull merges on the same branch kind of obfuscate resp. complicate history reading. Plus if you look on a merge commit (eg in gitlab) you see rather changes first that do not come from the author of the merge commit. Wouldn't it be a good strategy to fetch first and then decide whether to merge or rebase or even to create a branch from where you started your work first? – grenix Nov 26 '21 at 12:52

-

1@ThomasH. Yes. Git-pull's man page says: "In its default mode, `git pull` is shorthand for `git fetch` followed by `git merge FETCH_HEAD`. ... With `--rebase`, it runs `git rebase` instead of `git merge`." – Kalinda Pride Dec 18 '21 at 01:34

-

@AlexeyZimarev could you please elaborate more on your comment? How is this answer preventing NDVCS users to properly understand the benefits of having proper branches? – Alex Che Jun 21 '23 at 15:49

You should use git pull --rebase when

- your changes do not deserve a separate branch

Indeed -- why not then? It's more clear, and doesn't impose a logical grouping on your commits.

Ok, I suppose it needs some clarification. In Git, as you probably know, you're encouraged to branch and merge. Your local branch, into which you pull changes, and remote branch are, actually, different branches, and git pull is about merging them. It's reasonable, since you push not very often and usually accumulate a number of changes before they constitute a completed feature.

However, sometimes--by whatever reason--you think that it would actually be better if these two--remote and local--were one branch. Like in SVN. It is here where git pull --rebase comes into play. You no longer merge--you actually commit on top of the remote branch. That's what it actually is about.

Whether it's dangerous or not is the question of whether you are treating local and remote branch as one inseparable thing. Sometimes it's reasonable (when your changes are small, or if you're at the beginning of a robust development, when important changes are brought in by small commits). Sometimes it's not (when you'd normally create another branch, but you were too lazy to do that). But that's a different question.

- 167,292

- 40

- 290

- 283

- 96,026

- 17

- 121

- 165

-

25I think it is useful when you work on the same branch, but you may change your workstation. I tend to commit and push my changes from one workstation then pull rebase in the other, and keep working on the same branch. – Pablo Pazos Aug 03 '15 at 23:38

-

14It is a useful best practice to set up Git to automatically rebase upon pull with `git config --global pull.rebase preserve` (preserve says in addition to enabling rebasing, to try to preserve merges if you have made any locally). – Colin D Bennett Apr 08 '16 at 19:24

-

4I disagree that you should use pull --rebase only when working on one branch. You should use it all the time, unless impossible because of some other circumstance. – Tomáš Fejfar Jun 27 '18 at 14:28

-

1@P Shved... 'However, sometimes--by whatever reason--you think that it would actually be better if these two--remote and local--were one branch'...can this be done?My understadning is that in local environment, I can have my branch and a remote branch mirror as origin/master. Can yuo please provide inputs here? – Mandroid Jul 18 '18 at 12:11

-

2

-

1@ColinDBennett apparently, `pull.rebase preserve` option is no longer supported by git. It seems to be replaced by `merge` option with the same effect. Or maybe you made a typo initially, typing `preserve` instead of `merge`. :) https://git-scm.com/docs/git-config#Documentation/git-config.txt-pullrebase - https://git-scm.com/docs/git-pull#Documentation/git-pull.txt---rebasefalsetruemergesinteractive – mr.b Jan 12 '22 at 23:09

Perhaps the best way to explain it is with an example:

- Alice creates topic branch A, and works on it

- Bob creates unrelated topic branch B, and works on it

- Alice does

git checkout master && git pull. Master is already up to date. - Bob does

git checkout master && git pull. Master is already up to date. - Alice does

git merge topic-branch-A - Bob does

git merge topic-branch-B - Bob does

git push origin masterbefore Alice - Alice does

git push origin master, which is rejected because it's not a fast-forward merge. - Alice looks at origin/master's log, and sees that the commit is unrelated to hers.

- Alice does

git pull --rebase origin master - Alice's merge commit is unwound, Bob's commit is pulled, and Alice's commit is applied after Bob's commit.

- Alice does

git push origin master, and everyone is happy they don't have to read a useless merge commit when they look at the logs in the future.

Note that the specific branch being merged into is irrelevant to the example. Master in this example could just as easily be a release branch or dev branch. The key point is that Alice & Bob are simultaneously merging their local branches to a shared remote branch.

- 725

- 6

- 13

- 7,690

- 3

- 27

- 22

-

6Nice. I tend to be explicit and `git co master && git pull; git checkout topic-branch-A; git rebase master; git checkout master; git merge topic-branch-A; git push origin master` and repeat if another's push to master happened before mine. Though i can see the succinct advantages in your recipe. – HankCa Dec 19 '17 at 23:16

-

6"Alice's commit is applied after Bob's commit" perhaps worth noting the commit hash of Alice's commit does change in this case. – jiggunjer Feb 04 '21 at 10:51

-

1

-

1I don't understand. If the content modified by two people is not related, there should be no conflict between the modified content. Why is push not allowed in this case? – 时间只会一直走 Feb 22 '23 at 02:43

I think you should use git pull --rebase when collaborating with others on the same branch. You are in your work → commit → work → commit cycle, and when you decide to push your work your push is rejected, because there's been parallel work on the same branch. At this point I always do a pull --rebase. I do not use squash (to flatten commits), but I rebase to avoid the extra merge commits.

As your Git knowledge increases you find yourself looking a lot more at history than with any other version control systems I've used. If you have a ton of small merge commits, it's easy to lose focus of the bigger picture that's happening in your history.

This is actually the only time I do rebasing(*), and the rest of my workflow is merge based. But as long as your most frequent committers do this, history looks a whole lot better in the end.

(*)

While teaching a Git course, I had a student arrest me on this, since I also advocated rebasing feature branches in certain circumstances. And he had read this answer ;) Such rebasing is also possible, but it always has to be according to a pre-arranged/agreed system, and as such should not "always" be applied. And at that time I usually don't do pull --rebase either, which is what the question is about ;)

- 30,738

- 21

- 105

- 131

- 75,535

- 32

- 152

- 208

-

4

-

4Merges can contain diffs too, which means it's not entirely trivial – krosenvold Mar 19 '10 at 05:52

-

11

-

This answer is vague and opinionated in comparison with the chosen answer: what do you mean by "same branch" exactly? There are some good points, that are not in the chosen answer however. – iwein Jun 05 '11 at 12:32

-

2The vagueness around "branch" is quite intentional, since there are so many ways to use refs; "line of work" is just one option. – krosenvold Jun 05 '11 at 19:38

-

@hasen looks like `git log --no-merges` is just a workaround for an issue that can be easily avoided. – Victor Yarema Feb 02 '16 at 14:09

Just remember:

- pull = fetch + merge

- pull --rebase = fetch + rebase

So, choose the way what you want to handle your branch.

You'd better know the difference between merge and rebase :)

- 957

- 9

- 9

I don't think there's ever a reason not to use pull --rebase -- I added code to Git specifically to allow my git pull command to always rebase against upstream commits.

When looking through history, it is just never interesting to know when the guy/gal working on the feature stopped to synchronise up. It might be useful for the guy/gal while he/she is doing it, but that's what reflog is for. It's just adding noise for everyone else.

- 30,738

- 21

- 105

- 131

- 89,080

- 21

- 111

- 133

-

3"When looking through history, it is just never interesting to know when the guy working on the feature stopped to sync up." / but doesn't that mean those intermediate commits are likely broken builds? – eglasius Sep 24 '11 at 21:37

-

15Yes, and they're also not a "whole state". That's why we don't want them. I want to know what he wanted, not how he got there. – Dustin Sep 25 '11 at 22:09

-

8If `pull --rebase` should always be used, why doesn't `pull` do it by default? – straya Nov 01 '16 at 05:54

-

@straya it's default on all my repos, but some people have vastly different, very strange (to me) preferences. Defaults are not right in many ways. e.g., merge doesn't include summaries by default and non-annotated tags are almost never what you want. – Dustin Nov 04 '16 at 00:00

-

@Dustin appreciate your response and needs, to me it seems odd though - if it is a no-brainer that `pull --rebase` always be used while not doing so is "strange", surely Git should do the no-brainer way by default. And since it doesn't, it makes me question your assertion. – straya Nov 04 '16 at 09:11

-

3I'm afraid you're going to have to form your own opinion. I've got several things in my `.gitconfig` to make some of the options do the right thing. I think git rebase does the wrong thing by default, as does git tag, etc... If you disagree, you don't need to justify your opinion. – Dustin Nov 07 '16 at 16:31

-

13That seems good advice if you pull from "upstream", say from `master`, and if the branch you pull into hasn't gone public (yet). If you pull on the other hand from a feature branch into `master` it's more like the other way around: there's never a reason to use `--rebase`, right? That might be the reason why it is not default. _I found Rebases are how changes should pass from the top of hierarchy downwards and merges are how they flow back upwards._ https://www.derekgourlay.com/blog/git-when-to-merge-vs-when-to-rebase/ – jolvi Nov 17 '16 at 01:18

-

@jolvi I like " I found Rebases are how changes should pass from the top of hierarchy downwards and merges are how they flow back upwards". Nice way of describing it. The great thing about git is that it is suitable for beginners and advanced users. Always rebasing is not suitable for beginners. Rebassing at all is dicey if you don't understand about history. But once you do understand, suddenly you can use succinct commands and show a clean history. Best of both worlds. – HankCa Dec 19 '17 at 23:23

Edit:

Please do not use --rebase as a default as suggested by some other answers, you could lose some of your work. Example:

- A collaborator pushes commit 1

- On the same branch, you push commit 2

- The collaborator, without pulling your work, amends commit 1 and

git push --forceit (not a nice thing to do, but you are not in control here) - If you

git pull --rebase, you will silently lose commit 2 with all the work it contained.

I recommend using git pull --rebase only if you know you forgot to push your commits before someone else does the same.

If you did not commit anything, but your working space is not clean, just git stash before git pull, then git stash pop. This way you won't silently rewrite your history which could silently drop some of your work.

- 1,274

- 17

- 26

-

-

5@user18099 let's say you (A) and somebody else (B) are working on the same branch. B pushes their commit 1, you push your commit 2, and B, without pulling your work, amends their commit 1 and then push force. If you pull rebase, you will lose commit 2 with all the work it contained. – Habax Jun 27 '22 at 12:33

-

2

-

1You do not "silently lose commit 2" in the scenario you described. The diff between commit 2 and the amended commit 1 from origin is still applied locally during the rebase steps. You don't lose your work. – Tony B Jun 03 '23 at 05:02

How to Use git pull

git pull: Update your local working branch with commits from the remote, and update all remote tracking branches.git pull --rebase: Update your local working branch with commits from the remote, but rewrite history so any local commits occur after all new commits coming from the remote, avoiding a merge commit.git pull --force: This option allows you to force a fetch of a specific remote tracking branch when using the option that would otherwise not be fetched due to conflicts. To force Git to overwrite your current branch to match the remote tracking branch, read below about using git reset.git pull --all: Fetch all remotes - this is handy if you are working on a fork or in another use case with multiple remotes.

- 2,703

- 2

- 24

- 29

I think it boils down to a personal preference.

Do you want to hide your silly mistakes before pushing your changes? If so, git pull --rebase is perfect. It allows you to later squash your commits to a few (or one) commits. If you have merges in your (unpushed) history, it is not so easy to do a git rebase later one.

I personally don't mind publishing all my silly mistakes, so I tend to merge instead of rebase.

- 30,738

- 21

- 105

- 131

- 161,647

- 65

- 194

- 231

-

14Note to anyone viewing this question: this answer is completely irrelevant to the question "when should I use git pull --rebase?" – therealklanni Jan 18 '14 at 17:24

-

4@therealklanni I edited the answer so it gets clearer how it is relevant to the question (hopefully without destroying the intent). – Paŭlo Ebermann Jan 30 '14 at 12:53

-

2Sharing a dirty and unstructured work-log is not a honest endeavor, it's just laziness. You're wasting peoples time by making them chase you through your rabbit hole of development and debugging; give them the result, not the ramblings. – krystah Apr 09 '20 at 20:50

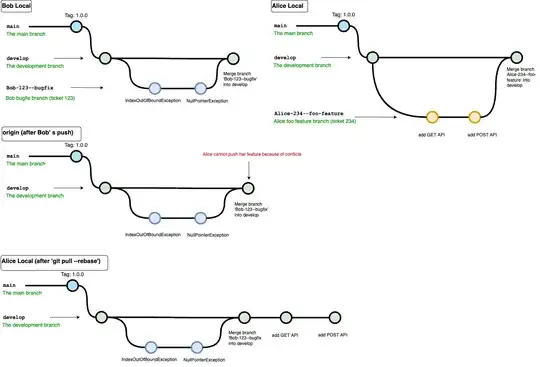

This scenario describes a situation where you cannot push your commits because the code on origin is changed. It is easy to understand Cody' s explanation. I draw a diagram to describe the scenario and hope it is helpful. If I am wrong, please correct me.

- 432

- 1

- 3

- 8

One practice case is when you are working with Bitbucket PR. Let's understand it with the below case:

There is PR open.

Then you decided to rebase the PR remote branch with the latest Master branch through BitBucket GUI. This action will change the commits' ids of your PR.

Since you have rebased the remote branch using GUI. first, you have to sync the local branch on your PC with the remote branch.

In this case git pull --rebase works like magic.

After git pull --rebase your local branch and remote branch have same history with the same commit ids.

Then now if you add a new commit/changes to the PR branch.

You can nicely push a new commit without using force or anything to remote branch/BitBucket PR.

- 582

- 8

- 10