The response by @romen is useful in discussing the overall ideas. In terms of concretely doing the locking, let's look at a few different situations and solutions. I'm assuming that we are using C# here. In addition I will generally take the perspective of writing a class that needs to use locking within itself to make sure that consistency is preserved.

Thread locking only. In this scenario, you have multiple threads and only want to prevent two different threads from altering the same part of memory (say a double) at the same time, which would result in corrupted memory. You can just use the "lock" statement in C#. HOWEVER, in contemporary programming environments this is not as useful as you might think. The reason is that within a "lock" statement there are a variety of ways of calling back into external code (i.e. code that is outside the class) and this external code may then call back into the lock (possibly asynchronously). In that situation the second time the "lock" statement is encountered, the flow may well pass right into the lock, regardless of the fact that the lock was already obtained. This is often not at all what you want. It will happen whenever the second call on the lock happens to occur on the same thread as the first call. And that can happen quite easily because C# is full of Tasks, which are basically units of work that can execute, block for other Tasks, etc all on a single thread.

Task locking for the purpose of preserving the state consistency of the object. In this scenario, there are a set of private fields within the class that must have a certain invariant relationship to each other both before and after each class method is called. The changes to these variables is done through straight-line code, specifically with no callbacks to code outside of the class and no asynchronous operations. An example would be a concurrent linked list, say, where there is a _count field and also _head and _tail pointers that need to be consistent with the count. In this situation a good approach is to use SemaphoreSlim in a synchronous manner. We can wrap it in a few handy classes like this --

public struct ActionOnDispose : IDisposable

{

public ActionOnDispose(Action action) => this.Action = action;

private Action Action { get; }

public void Dispose() => this.Action?.Invoke();

}

public class StateLock

{

private SemaphoreSlim Semaphore { get; } = new SemaphoreSlim(1, 1);

public bool IsLocked => this.Semaphore.CurrentCount == 0;

public ActionOnDispose Lock()

{

this.Semaphore.Wait();

return new ActionOnDispose(() => this.Semaphore.Release());

}

}

The point of the StateLock class is that the only way to use the semaphore is by Wait, and not by WaitAsync. More on this later. Comment: the purpose of ActionOnDispose is to enable statements such as "using (stateLock.Lock()) { … }".

- Task-level locking for the purpose of preventing re-entry into methods, where within a lock the methods may invoke user callbacks or other code that is outside the class. This would include all cases where there are asynchronous operations within the lock, such as "await" -- when you await, any other Task may run and call back into your method. In this situation a good approach is to use SemaphoreSlim again but with an asynchronous signature. The following class provides some bells and whistles on what is essentially a call to SemaphoreSlim(1,1).WaitAsync(). You use it in a code construct like "using (await methodLock.LockAsync()) { … }". Comment: the purpose of the helper struct is to prevent accidentally omitting the "await" in the using statement.

public class MethodLock

{

private SemaphoreSlim Semaphore { get; } = new SemaphoreSlim(1, 1);

public bool IsLocked => this.CurrentCount == 0;

private async Task<ActionOnDispose> RequestLockAsync()

{

await this.Semaphore.WaitAsync().ConfigureAwait(false);

return new ActionOnDispose( () => this.Semaphore.Release());

}

public TaskReturningActionOnDispose LockAsync()

{

return new TaskReturningActionOnDispose(this.RequestLockAsync());

}

}

public struct TaskReturningActionOnDispose

{

private Task<ActionOnDispose> TaskResultingInActionOnDispose { get; }

public TaskReturningActionOnDispose(Task<ActionOnDispose> task)

{

if (task == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("task"); }

this.TaskResultingInActionOnDispose = task;

}

// Here is the key method, that makes it awaitable.

public TaskAwaiter<ActionOnDispose> GetAwaiter()

{

return this.TaskResultingInActionOnDispose.GetAwaiter();

}

}

What you don't want to do is freely mix together both LockAsync() and Lock() on the same SemaphoreSlim. Experience shows that this leads very quickly to a lot of difficult-to-identify deadlocks. On the other hand if you stick to the two classes above you will not have these problems. It is still possible to have deadlocks, for example if within a Lock() you call another class method that also does a Lock(), or if you do a LockAsync() in a method and then the called-back user code tries to re-enter the same method. But preventing those reentry situations is exactly the point of the locks -- deadlocks in these cases are "normal" bugs that represent a logic error in your design and are fairly straightforward to deal with. One tip for this, if you want to easily detect such deadlocks, what you can do is before actually doing the Wait() or WaitAsync() you can first do a preliminary Wait/WaitAsync with a timeout, and if the timeout occurs print a message saying there is likely a deadlock. Obviously you would do this within #if DEBUG / #endif.

Another typical locking situation is when you want some of your Task(s) to wait until a condition is set to true by another Task. For example, you may want to wait until the application is initialized. To accomplish this, use a TaskCompletionSource to create a wait flag as shown in the following class. You could also use ManualResetEventSlim but if you do that then it requires disposal, which is not convenient at all.

public class Null { private Null() {} } // a reference type whose only possible value is null.

public class WaitFlag

{

public WaitFlag()

{

this._taskCompletionSource = new TaskCompletionSource<Null>(TaskCreationOptions.RunContinuationsAsynchronously);

}

public WaitFlag( bool value): this()

{

this.Value = value;

}

private volatile TaskCompletionSource<Null> _taskCompletionSource;

public static implicit operator bool(WaitFlag waitFlag) => waitFlag.Value;

public override string ToString() => ((bool)this).ToString();

public async Task WaitAsync()

{

Task waitTask = this._taskCompletionSource.Task;

await waitTask;

}

public void Set() => this.Value = true;

public void Reset() => this.Value = false;

public bool Value {

get {

return this._taskCompletionSource.Task.IsCompleted;

}

set {

if (value) { // set

this._taskCompletionSource.TrySetResult(null);

} else { // reset

var tcs = this._taskCompletionSource;

if (tcs.Task.IsCompleted) {

bool didReset = (tcs == Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref this._taskCompletionSource, new TaskCompletionSource<Null>(TaskCreationOptions.RunContinuationsAsynchronously), tcs));

Debug.Assert(didReset);

}

}

}

}

}

- Lastly, when you want to atomically test and set a flag. This is useful when you want to execute an operation only if it is not already being executed. You could use the StateLock to do this. However a lighter-weight solution for this specific situation is to use the Interlocked class. Personally I find Interlocked code is confusing to read because I can never remember which parameter is being tested and which is being set. To make it into a TestAndSet operation:

public class InterlockedBoolean

{

private int _flag; // 0 means false, 1 means true

// Sets the flag if it was not already set, and returns the value that the flag had before the operation.

public bool TestAndSet()

{

int ifEqualTo = 0;

int thenAssignValue = 1;

int oldValue = Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref this._flag, thenAssignValue, ifEqualTo);

return oldValue == 1;

}

public void Unset()

{

int ifEqualTo = 1;

int thenAssignValue = 0;

int oldValue = Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref this._flag, thenAssignValue, ifEqualTo);

if (oldValue != 1) { throw new InvalidOperationException("Flag was already unset."); }

}

}

I would like to say that none of the code above is brilliantly original. There are many antecedents to all of them which you can find by searching enough on the internet. Notable authors on this include Toub, Hanselman, Cleary, and others. The "interlocked" part in WaitFlag is based on a post by Toub, I find it a bit mind-bending myself.

Edit: One thing I didn't show above is what to do when, for example, you absolutely have to lock synchronously but the class design requires MethodLock instead of StateLock. What you can do in this case is add a method LockOrThrow to MethodLock which will test the lock and throw an exception if it cannot be obtained after a (very) short timeout. This allows you to lock synchronously while preventing the kinds of problems that would occur if you were mixing Lock and LockAsync freely. Of course it is up to you to make sure that the throw doesn't happen.

Edit: This is to address the specific concepts and questions in the original posting.

(a) How to protect the critical section in the method. Putting the locks in a "using" statement as shown below, you can have multiple tasks calling into the method (or several methods in a class) without any two critical sections executing at the same time.

public class ThreadSafeClass {

private StateLock StateLock { get; } = new StateLock();

public void FirstMethod(string param)

{

using (this.StateLock.Lock()) {

** critical section **

// There are a lot of methods calls but not to other locked methods

// Switch cases, if conditions, dictionary use, etc -- no problem

// But NOT: await SomethingAsync();

// and NOT: callbackIntoUserCode();

** critical section **

}

}

public void SecondMethod()

{

using (this.StateLock.Lock()) {

** another, possibly different, critical section **

}

}

}

public class ThreadSafeAsyncClass {

private MethodLock MethodLock { get; } = new MethodLock();

public async Task FirstMethodAsync(string param)

{

using (await this.MethodLock.LockAsync()) {

** critical section **

await SomethingAsync(); // OK

callbackIntoUserCode(); // OK

}

}

public async Task SecondMethodAsync()

{

using (await this.MethodLock.LockAsync()) {

** another, possibly different, critical section using async **

}

}

}

(b) Could delegates help, given that Delegate is a thread-safe class? Nope. When we say that a class is thread-safe, what it means is that it will successfully execute multiple calls from multiple threads (usually they actually mean Tasks). That's true for Delegate; since none of the data in the Delegate is changeable, it is impossible for that data to become corrupted. What the delegate does is call a method (or block of code) that you have specified. If the delegate is in the process of calling your method, and while it is doing that another thread uses the same delegate to also call your method, then the delegate will successfully call your method for both threads. However, the delegate doesn't do anything to make sure that your method is thread-safe. When the two method calls execute, they could interfere with each other. So even though Delegate is a thread-safe way of calling your method, it does not protect the method. In summary, delegates pretty much never have an effect on thread safety.

(c) The diagram and correct use of the lock. In the diagram, the label for "thread safe section" is not correct. The thread safe section is the section within the lock (within the "using" block in the example above) which in the picture says "Call Method". Another problem with the diagram is it seems to show the same lock being used both around the Call Method on the left, and then also within the Method on the right. The problem with this is that if you lock before you call the method, then when you get into the method and try to lock again, you will not be able to obtain the lock the second time. (Here I am referring to task locks like StateLock and MethodLock; if you were using just the C# "lock" keyword then the second lock would do nothing because you would be invoking it on the same thread as the first lock. But from a design point of view you wouldn't want to do this. In most cases you should lock within the method that contains the critical code, and should not lock outside before calling the method.

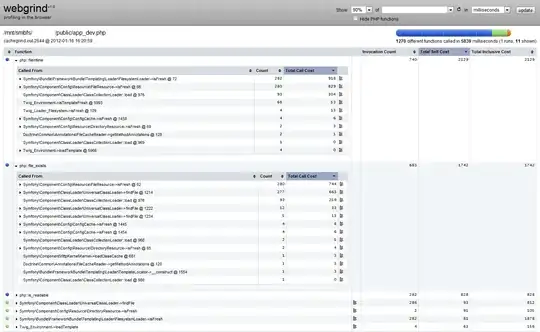

(d) Is Lock or Mutex faster. Generally the speed question is hard because it depends on so many factors. But broadly speaking, locks that are effective within a single process, such as SemaphoreSlim, Interlocked, and the "lock" keyword, will have much faster performance than locks that are effective across processes, like Semaphore and Mutex. The Interlocked methods will likely be the fastest.

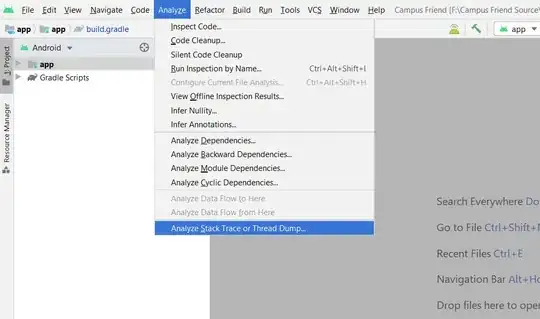

(e) Identifying shared resources and whether visual studio can identify them automatically. This is pretty much intrinsic to the challenge of designing good software. However if you take the approach of wrapping your resources in thread-safe classes then there will be no risk of any code accessing those resources other than through the class. That way, you do not have to search all over your code base to see where the resource is accessed and protect those accesses with locks.

(f) How to release a lock after 2.5 seconds and queue other requests to access the lock. I can think of a couple of ways to interpret this question. If all you want to do is make other requests wait until the lock is released, and in the lock you want to do something that takes 2.5 seconds, then you don't have to do anything special. For example in the ThreadSafeAsyncClass above, you could simply put "await Task.Delay( Timespan.FromSeconds(2.5))" inside the "using" block in FirstMethodAsync. When one task is executing "await FirstMethodAsync("")" then other tasks will wait for the completion of the first task, which will take about 2.5 seconds. On the other hand if what you want to do is have a producer-consumer queue then what you should do is use the approach described in StateLock; the producer should obtain the lock just briefly while it is putting something into the queue, and the consumer should also obtain the lock briefly while it is taking something off the other end of the queue.